Wisdom Publications Presents

Bhikkhu Anālayo Resources

A Snapshot of Ven. Anālayo's Work

These key Buddhist resources from eminent teacher Bhikku Anālayo are intended to enhance awareness of the many books, podcasts, videos, lectures, and online courses available in Wisdom’s catalog of Buddhist content. We hope that you enjoy what’s on offer here!

Video Teachings

We offer you the following two video teachings from Bhikku Anālayo:

[1] A Personal History of Academic Research: Ven. Anālayo presents the history of his research into Early Buddhism.

[2] Meditation in Early Buddhism: Ven. Anālayo explores The Shorter Discourse on Emptiness, looking at the universality of the practice of abiding in emptiness throughout Buddhist traditions.

Keep Up To Date

Enjoy Bhikku Anālayo’s books and video teachings? If you want to periodically receive free Anālayo content and exclusive offers, simply enter your first name and email address below. Your inbox will not be spammed.

If you don’t see our initial confirmation email in your inbox, kindly check your spam folder.

Excerpts from Anālayo’s books

Bhikkhu Anālayo has written over five hundred publications that are for the most part based on comparative studies. He also has a special interest in topics related to meditation and the role of women in Buddhism. The passages/sections below are drawn from his books published with Wisdom, which number six in total.

This excerpt is from Ven. Anālayo’s Abiding in Emptiness: A Guide for Meditative Practice, pp. 60-63.

THE PERCEPTION OF SPACE

Infinite space is the object of the first of the four immaterial spheres, the other three being infinite consciousness, nothingness, and neither-perception-nor-nonperception, each of which builds on having successfully mastered the previously mentioned immaterial sphere(s). The immaterial sphere of infinite space in turn appears to require mastery of the four absorptions. This is evident from listings of the four absorptions and the four immaterial spheres in a description of successive meditative abidings found in Pāli discourses and their parallels. The implication is that each item in the list requires previous attainment of the items mentioned earlier, which in the case of the immaterial sphere of infinite space are the four absorptions. The same can also be seen in a discourse extant in Pāli and Chinese that presents the fourth absorption as transcending the third (just as this transcends the second and the second transcends the first) and then the attainment of the sphere of infinite space as transcending the fourth absorption. Thus, just as attaining the fourth absorption would require the ability to attain the third, so attaining the sphere of infinite space would require the ability to attain the fourth absorption.

Mastery of the absorptions or any of the immaterial spheres also stands in relation to early Buddhist cosmology, in that each such attainment leads to rebirth in the corresponding realms. In the case of mastery of the sphere of infinite space, a Pāli discourse indicates that the lifespan of those reborn accordingly is twenty thousand eons. An eon corresponds to the time it would take to wear down a solid mountain several miles high by stroking it with a piece of cloth once every hundred years. It follows that a lifespan of twenty thousand eons stands for an incredibly long period of time.

The implications of the concentrative requirement for gaining mastery of the immaterial sphere of infinite space and its lofty rebirth prospects depend on assessing the nature of the fourth absorption. Contrary to a popular trend of presenting the four absorptions as something within easy reach of the average practitioner, a close comparative study of relevant passages in the early discourses conveys the impression that absorption attainment requires considerable meditative mastery.

Hence, the ability to attain the fourth absorption at will would be a matter of having acquired a high degree of expertise in concentration.

Nevertheless, a meditative cultivation of the notion of infinite space as such does not require that much, as is evident from its inclusion in the list of kasiṇas discussed in the previous chapter (see above p. 42). These are means to cultivate concentration in order to gain absorption and thus obviously can take place at levels of concentration that fall short of even the first absorption. A cultivation of the notion of space in a way that does not rely on previous absorption attainment appears to be indeed the perspective relevant to the passage translated above. Its formulation differs from the way the early discourses usually introduce the attainment of the sphere of infinite space. When referring to the sphere of infinite space, the present instruction does not indicate that one “abides in its attainment” (upasampajja viharati) but just that one has the corresponding “perception” (saññā). The Chinese and Tibetan versions agree in speaking just of having the “perception” (xiăng/’du shes). Arousing just the perception does not need previously developed absorption ability. It follows that such abilities would not be required in order to be able to execute the instructions given above. What does seem necessary is the absence of distraction to enable maintaining the perception of the sphere of infinite space. This much can be achieved through well-established mindfulness and dedicated practice.

Nevertheless, cultivating the perception of infinite space does require considerable meditative training, especially if we have not yet developed familiarity with leading the mind into a calm abiding without relying on a specific circumscribed focus, such as is possible through the boundless radiation of the divine abodes. For this reason, arousing and maintaining the perception of infinite space may at first subjectively appear challenging and for some time seem to be just an abstract concept. It needs time and dedication until the mind “enters upon, is pleased with, settles on, and is devoted to it,” terms that clearly point to the need for mental tranquility.

A cultivation of the perception of infinite space in formal meditation can benefit considerably from experimenting with the perception of space outside of formal meditation. An ideal occasion for doing that could take advantage of being in an open space on a cloudless day.

Positioning the body in as relaxed a manner as possible, perhaps even reclining or leaning back in a comfortable chair, we simply gaze at the sky in awareness of its infinite nature. However far the gaze reaches, it is not possible to find any limit to space. Such experimenting with the visual apperception of space in the sky can help us to arouse more easily the meditative notion of infinite space in formal meditation.

Another helpful tool for facilitating formal meditation can take the form of countering possible negative associations with space as being a mere absence. A simile found in a Pāli discourse and its Chinese parallel illustrates the nature of the body with the example of a house. Just as a house consists of space enclosed by building material, so the human body consists of space enclosed by skin, flesh, and bones. Although this is not the explicit purpose of the simile, in both cases the image shows that the respective space has an important function to fulfill. It is the space of the house that can be inhabited, not the building material. Even though we would normally be inclined to give all importance to the building material, on reflection it becomes clear that the space inside the house carries considerable importance. The same holds in turn for the human body. Here, too, we may tend to give all importance to the different organs. Yet, without the space to breathe in or to take in nourishment, the body could not function. Moreover, the greater part of human sensory experience depends on space and not just, as we may unthinkingly assume, on the functionality of the respective sense organs. If the space in front of the eyes is blocked, no seeing will be possible. If the space in the apertures of the ears, the nose, and the mouth is obstructed, hearing, smelling, and tasting will also not be possible, however much the senses themselves are functional. Reflecting along these lines can help to reveal the importance and also the enabling potential of space as that which facilitates a range of activities and events. Clearly, space is not just a blank nothing.

Another avenue for easing into the perception of infinite space can be the cultivation of the four divine abodes. When a boundless abiding in the divine abodes has been practiced, there is already a solid degree of familiarity with space as the field that is pervaded by each brahmavihāra, wherefore the perception of infinite space becomes considerably less challenging. This undermines a possible tendency in the mind of wanting to construct space, to make it happen in some way. For this reason, if the perception of infinite space should prove difficult, it can be helpful to dedicate time to a systematic development of all four divine abodes and, after familiarity with these has been achieved, to take boundless abiding in equanimity as the point of transition for attempting again to abide in the perception of infinite space.

The following is excerpted from Ven. Anālayo’s The Signless and the Deathless: On the Realization of Nirvana, pp. 8-17.

GRASPING AT SIGNS

A key dimension of the act of taking up a sign by an unawakened mind is the weaving of subjective evaluations into the process of perception, which usually happens in a way that is not consciously noticed. The early discourses point to such evaluations by speaking of the “sign of attraction” and the “sign of aversion,” for example. Whereas paying unwise attention to the former can trigger sensual desire, doing the same with the latter can result in the arising of ill will. This presentation alerts to the predicament inherent in the basic act of taking up a sign, central to the appraisal of the world through perception. The influence of the sign can trigger an unwholesome mental condition, and this often enough happens outside of the purview of conscious recognition. From the subjective viewpoint, beauty and ugliness, etc., are regarded as features of the objects out there, rather than acknowledged for what they truly are: evaluations that originate in one’s own mind.

The problem of evaluations rooted in unwholesome mental conditions comes to the fore in another passage extant in Pāli, according to which sensual lust, anger, and delusion are makers of signs. The Chinese parallel conveys the same basic idea, although it does not have an explicit counterpart to the idea of a “maker” of signs. The three root defilements are makers of signs (or just signs) in the sense that they can substantially impact how the world is experienced. They do so by influencing which signs are given attention, thereby making these stand out in the overall perceptual appraisal of any object or situation. Unless kept in check by mindfulness, these three quite literally construct one’s world. That which arouses sensual lust, anger, and delusion appears to be out there, when in reality it is in here, namely in the way perception has woven those signs into its appraisal of the world. Ñāṇananda reasons that to reckon the three root defilements as makers of signs

might appear, at first sight, a not-too-happy blend of philosophy and ethics. But there are deeper implications involved. It is a fact often overlooked by the metaphysician that the reality9attributed to sense-data is necessarily connected with their evocative power, that is, their ability to produce effects. The reality of a thing is usually registered in terms of its impact on the experiential side . . . Now, the “objects” of sense which we grasp . . . their significance depends on the psychological mainsprings of lust, hatred and delusion.

The role of defilements as makers of signs in turn relates to an elementary stage in the arising and gradual increase of defilements. Usually one does not consciously decide “let me now be lustful” or “be furious” or “be confused.” Instead, perception has identified something that triggers a defilement and, as the mind keeps returning to that, the defilement keeps increasing and coloring subsequent acts of perception. In this way, the three root defilements can indeed become makers of signs.

In contrast to this predicament stands the possibility of being “empty of sensual desire, anger, and delusion.” This is precisely the goal of early Buddhist meditative training, namely to empty the mind of defilements and thereby arrive at a way of apperceiving the world that better accords with reality and no longer is under the sway of these three signs. I will return to the relationship of such absence of defilements to liberation in the second part of my exploration.

The need to be wary of the impact of subjective evaluations and to keep the mind increasingly empty of defilements informs a foundational mindfulness-related practice known as sense restraint. Such practice needs to be differentiated from the idea that sense objects should just be avoided. The idea of merely curtailing sense experience comes up for criticism in a Pāli discourse and its Chinese parallel, which feature a young brahmin reporting his teacher’s injunctions in this respect. According to this teacher, one should just refrain from seeing forms with the eye and hearing sounds with the ear. Yet, the critical reply to this proposal clarifies that the solution is not to pretend to be blind or deaf. Instead, anything happening at a sense door needs to be monitored with mindfulness to avoid any grasping at signs that may cause unwholesome mental repercussions. How this can be achieved can be seen in actual instructions on sense restraint, taken from10a discourse preserved in Chinese, which proceed as follows for the sense door of the eye:

If seeing a form with the eye, however, do not grasp the sign and also do not savor the form . . . guard the eye faculty so that no greed or sorrow, bad and unwholesome states, arise in the mind.

The Pāli parallel, after similarly warning against grasping the sign, continues by extending this warning also to grasping any “secondary characteristic” (anuvyañjana). Such secondary characteristics tend to elaborate further the first impression created by the sign. Their function can conveniently be illustrated with the help of the phrase employed instead in the above-quoted Chinese counterpart, which speaks of “savoring” the object. In other words, the task is to avoid savoring what is being experienced, not keeping it on the tongue of the mind, so to say, comparable to delicious food.

The use of the term “grasping” in both versions can best be taken to convey the sense of latching on to the sign, by way of clinging to whatever associations it calls up. Someone who successfully practices sense restraint still sees, hears, etc. The information seen, heard, etc., is still processed by the mind in order to be understood, which requires reliance on signs. But mindfulness is sufficiently well established at that point to notice when such processing of the sensory data takes up biased signs and veers off into unwholesome territory.

Both versions explicitly highlight that the main purpose of sense restraint is precisely to avoid the arising of bad and unwholesome states. Noticing as soon as possible that a particular sign is triggering such unwholesome reactions would enable the exercise of restraint right there and then, by way of letting go of that type of sign and intentionally directing attention in a way that avoids savoring the corresponding secondary characteristics.

Such sense restraint can enable becoming increasingly conscious of the operation of those signs that potentially trigger an unwholesome reaction, thereby offering a foundational practice for learning to work with signs. A central implication of cultivating sense restraint in this respect would be an encouragement to realize when something causes strong repercussions within. This can then lead to investigating whether the evaluation underpinning those strong reactions realistically reflects the actual situation or whether it is, at least in part, due to projections and biases. Such projections and biases would be due to grasping at signs and savoring their secondary characteristics. The practice of sense restraint would thus help the practitioner to become increasingly aware of the way the mind is processing things under the impact of unwholesome projections and biases, thereby enabling a stepping out of such habitual patterns of reactivity and their detrimental consequences.

As an illustration of this first and foundational type of practice in relation to signs, lack of sense restraint could be compared to someone aimlessly surfing around on the internet, clicking here and there, at the mercy of whatever happens to appear on the screen. Establishing sense restraint could then be related to the case of someone who uses the web just to find a particular type of information, without getting sidetracked by whatever other things may be popping up here and there. Needless to say, the same contrast between aimless surfing and not getting sidetracked can also take place just in the mind, without any need to go online.

Building on the groundwork laid through sense restraint and standing in continuity with it, meditative training in relation to signs can then proceed to increasing levels of profundity with the practice of bare awareness, to be discussed below, and eventually with signless concentration. These mutually supportive practices can be seen to form part of a continuum of mental cultivation aimed at understanding and working with the way perception appraises the world. Before getting into those practices, however, first a closer look at the construction of experience is required.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF EXPERIENCE

The basic operation of the sign relates closely to how perception makes sense of, and thereby to a considerable degree constructs, the world of experience. In this respect, early Buddhist thought can be understood to take a middle position between realism and idealism. In short, the12existence of things outside of the purview of subjective apperception is not denied, but the way they are actually perceived is considered to be largely influenced by the mind.

A Pāli discourse, with parallels extant in Chinese and Sanskrit, reports the Buddha stating that the end of the world cannot be reached by walking, yet there is no making an end of dukkha/duḥkha without reaching the end of the world.

The parallel versions agree in showing the monastics in the audience to be at first unable to grasp the meaning of the Buddha’s succinct statement, presumably because they were taking the term “world” in its ordinary meaning. They reportedly approached the Buddha’s attendant Ānanda for clarification. Below is the central part from the Pāli version of his clarification.

Friends, that by which in the world one becomes a perceiver of the world and a conceiver of the world, that is called “the world” in the noble one’s discipline.

In the Pāli and Chinese versions, Ānanda continues by taking up each of the six senses individually—the five physical senses and the mind as the sixth—making clear how they all contribute to the construction of “the world.” The parallels report that his elucidation received the Buddha’s approval.

This reappraisal of the significance of the term “world” offers a key to understanding the meaning behind the succinct dictum that the end of the world cannot be reached by walking. It reflects a substantial shift of perspective from the assumption, presumably prevalent among the members of the audience of this discourse, that the world is as it appears to be out there. The teaching clearly draws attention to the degree to which the genesis of the world takes place in the mind, without going so far as to assert that there is nothing at all out there. The existence of something out there is in fact implicitly affirmed with the expression “that by which in the world one becomes a perceiver of the world.” The end of the world, when understood in this manner, will indeed not be reached by travelling to some external location. Instead, it is to be found within, namely by stepping out of the construction of the world.

Another Pāli discourse and one of its two Chinese parallels present what appears to be basically the same perspective by succinctly stating that “the world has arisen in the six.” This conveys that any experience of the external world arises through the activity of the six senses. It is precisely because what appears to be out there much rather originates right here that it can also be transcended right here. Tilakaratne sums up: “The subject is nothing other than a complex of reactions to the world (object); the world is nothing other than what is perceived by the subject.”

The same principle holds for the term “all,” in that such an expression simply covers the whole gamut of experience that is possible through the six sense spheres; in other words, “all” stays within the confines of subjective experience.

Yet another Pāli discourse and its Chinese parallel confirm that the term “world” stands for what is encountered through the six senses. Ñāṇananda offers the following comment on this notion of the world:

Thus the world is what our senses present it [to] us to be. However, the world is not purely a projection of the mind in the sense of a thoroughgoing idealism; only, it is a phenomenon which the empirical consciousness cannot get behind, as it is itself committed to it. One might, of course, transcend the empirical consciousness and see the world objectively in the light of paññā [wisdom] only to find that it is void (suñña) of the very characteristics which made it a “world” for oneself. To those who are complacently perched on their cosy conceptual superstructures regarding the world, there is no more staggering a revelation than to be told that the world is a void. They might recoil from the thought of being plunged into the abysmal depths of a void where concepts are no more. But one need not panic, for the descent to those depths is gradual and collateral with rewarding personal experience.

According to two different Pāli discourses and their parallels, the world is in fact led by the mind. The leading role taken by the mind in this way also comes up in a verse in the Dharmapada collections, whose Pāli version begins by stating that “the mind precedes phenomena,” dharmas, a proposition similarly found in several parallels. In fact, the Pāli version goes further by also qualifying phenomena to be “made by the mind.” The context shows that this is not meant to convey an idealistic sense. The statement in question occurs in two twin verses, which point out that doing evil leads to affliction just as doing good leads to happiness. In other words, the verses in question express in a poetical manner the basic teaching on karma and its fruit that is such a pervasive concern in the early texts.

This basic principle of karma is not confined to rebirth, as it can have repercussions visible in the same lifetime in which a particular deed was done. In fact, to some extent it can be considered to produce some effects immediately. The type of intention with which one approaches a particular situation will influence not only the way one acts but also the way one perceives (and inevitably evaluates) the actions and attitudes of others who are playing a part in the given situation. In this sense, then, the mind can indeed be considered the source of phenomena, and these are mind-made to a higher degree than one would normally be ready to admit.

Another relevant statement, found in a Pāli discourse and its Chinese parallel, presents the diversity observable among animals as a reflection of the diversity of the mind. The Pāli commentary explains this to refer to karma and its fruit, in the sense that the diversity observable among animals reflects the diversity of their deeds done intentionally in former lives. An alternative interpretation, presented by Ñāṇananda, proposes that this passage can be taken to refer to the constructing activity by those who perceive such diversity among animals:

Generally, we may agree that beings in the animal realm are the most picturesque. We sometimes say that the butterfly is beautiful. But we might hesitate to call a blue fly beautiful. The tiger is fierce, but the cat is not. Here one’s personal attitude accounts much for the concepts of beauty, ugliness, fierceness, and innocence of animals.

The nature of perception also comes up in the context of a set of similes, found similarly in a Pāli discourse and a range of parallels, which illustrate each of the five aggregates. Here, perception is comparable to a mirage (of the type that can appear in the Indian hot season). It projects something else on top of what is actually there. The same discourse also takes up the potentially deluding nature of consciousness, which is similar to a magical illusion (created by an illusionist). A mirage and an illusion turn out on close inspection to be void and without any essence. The same holds for these two aggregates, and even more so for their ability to mislead the mind into mistaken conclusions and evaluations.

A Pāli verse with several parallels even goes so far as to commend the understanding, in relation to the world, that “all this is unreal.” The indication given in this way needs to be handled with care in order to avoid reading too much into it. It is probably best read in line with the material surveyed so far, in the sense of drawing attention to the lack of reality of what has been constructed by the mirage of perception and the magical illusion of consciousness. Such an understanding can serve as a path to liberation, here expressed as a transcendence of both this shore and the other shore. The ensuing four verses in this Pāli collection keep returning to the significance of understanding that “all this is unreal,” relating such insight to freedom from greed, sensual lust, anger, and delusion, respectively. The context suggests that this serves as a strategy to wean the mind from taking things too seriously, something that is particularly prone to happen when defilements manifest. A brief reminder of the lack of reality of what has been conjured up by the mirage of perception and the magical illusion of consciousness can offer substantial help to sap the power of the forces of greed, sensual desire, anger, and delusion.

The construction of experience appears to be the main theme of a passage that puts a spotlight on the role of the fourth aggregate (saṅkhāras or saṃskāras) in this respect. According to the relevant Pāli version, whose presentation in this respect finds confirmation in counterparts extant in Chinese and Tibetan, the fourth aggregate performs the following role in relation to each of the five aggregates:

Monastics, “they construct the constructed,” therefore they are called volitional constructions. And what is the constructed which they construct? Bodily form, which is constructed, they construct into bodily form; feeling tone, which is constructed, they construct into feeling tone; perception, which is constructed, they construct into perception; volitional constructions, which are constructed, they construct into volitional constructions; consciousness, which is constructed, they construct into consciousness. Monastics, “they construct the constructed,” therefore they are called volitional constructions.

The key term here is Pāli saṅkhāra or Sanskrit saṃskāra, which can be rendered in a range of different ways. For the purpose of my present exploration, I have chosen the rendering “volitional constructions,” without thereby intending to present this as the one and only choice. The Indic term is too multivalent for a single English counterpart to be able to convey all of its nuances, and in other contexts the more commonly used “volitional activities,” “volitional formations,” or even just “formations” can indeed be the preferable option.

As regards the role saṅkhāras/saṃskāras play in the above passage, one relevant dimension would again be the perspective of karma and its fruit. However, the passage occurs in the context of a survey of characteristic functions of each of the five aggregates, and the operation of the fourth aggregate is not confined to the effect of what has been done in the past. From this perspective, then, it seems meaningful to interpret this passage as pointing to the role of saṅkhāras/saṃskāras in the construction of experience in the present. On this understanding, these saṅkhāras/saṃskāras can be seen to perform their role continuously, that is, in every moment of experience. As long as their constructing activity is based on ignorance (the first link in the standard presentation of dependent arising that leads on to saṅkhāras/saṃskāras as its second link), such construction is inevitably bound to result in the manifestation of dukkha/duḥkha.

The need to become aware of the construction of experience, which seems to emerge as a common theme in the selected passages surveyed above, has a counterpart in the findings of modern psychology. Feldman Barret explains that “we humans are architects of our own experiences . . . We actively participate in constructing our experiences even though we are mostly unaware of that fact.” Although this may at first sight seem counterintuitive, the truth of the matter is that the world of experience is to a considerable degree a construct of the mind:

Your perceptions are so vivid and immediate that they compel you to believe that you experience the world as it is, when you actually experience a world of your own construction. Much of what you experience as the outside world begins inside your head.

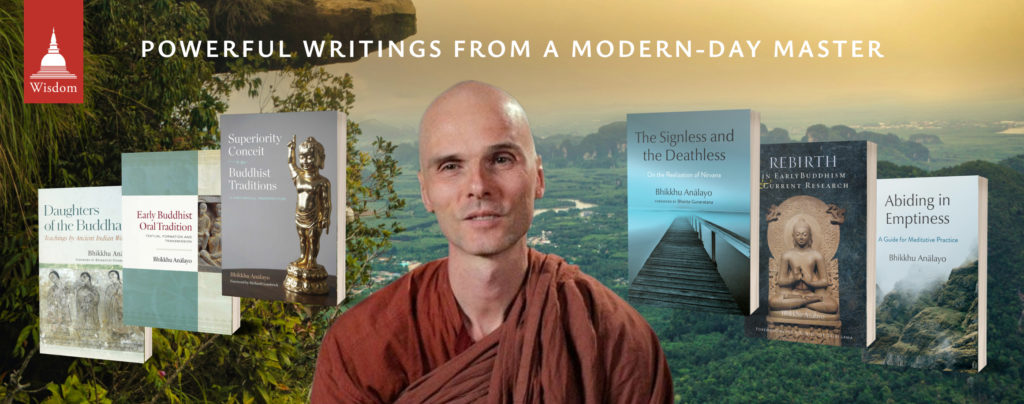

About the Teacher

The free resources shared on this page are from Wisdom’s projects in collaboration with Bhikkhu Anālayo.

Bhikkhu Anālayo is a scholar of early Buddhism and a meditation teacher. He completed his PhD research on the Satipaṭṭhānasutta at the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka, in 2000 and his habilitation research with a comparative study of the Majjhimanikāya in light of its Chinese, Sanskrit, and Tibetan parallels at the University of Marburg, Germany, in 2007. His over five hundred publications are for the most part based on comparative studies, with a special interest in topics related to meditation and the role of women in Buddhism.

Bhikkhu Anālayo is a scholar of early Buddhism and a meditation teacher. He completed his PhD research on the Satipaṭṭhānasutta at the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka, in 2000 and his habilitation research with a comparative study of the Majjhimanikāya in light of its Chinese, Sanskrit, and Tibetan parallels at the University of Marburg, Germany, in 2007. His over five hundred publications are for the most part based on comparative studies, with a special interest in topics related to meditation and the role of women in Buddhism.