Beata Grant

Beata Grant is professor of Chinese and Religious Studies (Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures) at Washington University. She lives in St. Louis, Missouri.

Books, Courses & Podcasts

Daughters of Emptiness

Printed on demand. This book will be printed especially for you and will ship from a separate warehouse.

Women played major roles in the history of Buddhist China, but given the paucity of the remaining records, their voices have all but faded. In Daughters of Emptiness, Beata Grant renders a great service by recovering and translating the enchanting verse—by turns assertive, observant, devout—of forty-eight nuns from sixteen centuries of imperial China. This selection of poems, along with the brief biographical accounts that accompany them, affords readers a glimpse into the extraordinary diversity and sometimes startling richness of these women’s lives.

A sample poem for this stunning collection:

The sequence of seasons naturally pushes forward,

Suddenly I am startled by the ending of the year.

Lifting my eyes I catch sight of the winter crows,

Calling mournfully as if wanting to complain.

The sunlight is cold rather than gentle,

Spreading over the four corners like a cloud.

A cold wind blows fitfully in from the north,

Its sad whistling filling courtyards and houses.

Head raised, I gaze in the direction of Spring,

But Spring pays no attention to me at all.

Time a galloping colt glimpsed through a crack,

The tap [of Death] at the door has its predestined time.

How should I not know, one who has left the world,

And for whom floating clouds are already familiar?

In the garden there grows a rosary-plum tree:

Whose sworn friendship makes it possible to endure.

—Chan Master Jingnuo

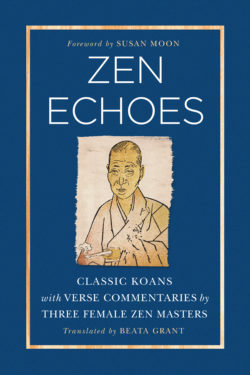

Zen Echoes

Too often the history of Zen seems to be written as an unbroken masculine line: male teacher to male student. In this timely volume, Beata Grant shows us that women masters do exist—and have always existed.

Zen Echoes is a collection of classic koans from Zen’s Chinese history that were first collected and commented on by Miaozong, a twelfth-century nun so adept that her teacher, the legendary Dahui Zonggao, used to tell other students that perhaps if they practiced hard enough, they might be as realized as her.

Nearly five hundred years later, the seventeenth-century nuns Baochi and Zukui added their own commentaries to the collection. The three voices—distinct yet harmonious—remind us that enlightenment is at once universal and individual.

In her introduction to this shimmering translation, Professor Grant tells us that the verses composed by these women provide evidence that “in a religious milieu made up overwhelmingly of men, there were women who were just as dedicated to Chan practice, just as advanced in their spiritual realization, and just as gifted at using language to convey that which is beyond language.”