Shantideva was a monk at the famed Nalanda University. Outwardly Shantideva showed no signs of being a great master. In fact the monks living in the monastery gave him the name Busuku, which means the one who only does three things: eat, sleep, and make ka-ka. They never saw him reading texts or engaging in religious activity. They felt he was just wasting monk community resources that had been offered with devotion by benefactors. When monks do not practice the Dharma or keep the precepts well but just use things offered by benefactors, they create much negative karma.

Therefore many felt Shantideva should be driven out of the monastery. They saw him as useless. A group of monks contrived a plan to drive him out by ridiculing him. They based their plan on a practice whereby monks have to memorize many sutra texts and then recite them before an assembly of monks. The group thought that Shantideva would be unable to do this, which would be a reason to expel him.

The invitation was made to Shantideva and he accepted. In a mocking way, the monks created a very high teaching throne for Shantideva to sit on, expecting he wouldn’t be able to do even that.

But when the time came, Shantideva ascended the throne without any difficulty. He then asked the audience, “Should I recite a sutra text that you all know, or one that has not yet been heard?” The audience replied, “Please give a teaching on a text that has not been heard.”

Shantideva then delivered what has become the renowned Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life (Skt. Bodhicaryavatara), which contains the 84,000 teachings of the Buddha in a simple and easy-to-understand way. The ten chapters of the text include a chapter on the cultivation of wisdom, shunyata. While Shantideva was teaching this chapter, he levitated higher and higher until he was no longer visible to the audience, although his voice was still clearly audible. The recitation showed not only Shantideva’s profound knowledge of the Buddha’s teachings but also his great supernormal powers. After this public incident, all of Nalanda realized the great being they had in their midst.

The essential way to practice exchanging self for others is to regard the suffering of others exactly as our own suffering and to help others as if they were ourselves. We need to completely change our old motives and selfish actions! Abandoning self-cherishing and cherishing only others is the bodhicitta method. Nurture the mind that cares only about alleviating the suffering of others with a sincere, generous, and uncrooked attitude. This is how the bodhisattva acts, renouncing himself and focusing only on the well-being of others.

We are nowhere near approximating this state of mind. Every time we encounter any living being in hardship, we should feel as if that other being’s body and mind are our own. We need to cultivate this attitude to the point where we experience whatever is happening to that other being’s body and mind as also happening to us. If we do not equalize others with ourselves, many realizations will not come.

We can mentally picture a bodily injury like a toothache and feel the pain from that, so why not do the same about the pain of others? We can train our minds to feel another’s bodily sensations or mental anguish as our own. Originally our body was linked to our father’s and mother’s bodies, but the mind learned to regard it as our own, thinking, “This is me.” Why does such a concept arise so early and so strongly? Why do we take such good care of this body?

The answer is that we have become habituated to thoughts like “This is me” and “This is my body” since beginningless lives. We have excelled in training the mind to grasp at the “I.” We take better care of this body than we do our parents’ bodies, even though ours began from theirs. Exchanging oneself for others is an essential bodhisattva practice to achieve ultimate happiness for ourselves and others.

We may be surprised to hear how the Buddha first generated compassion in the hell realm. In one of his past lives the Buddha was born in a hell realm, pulling a carriage alongside another hell being, like two buffaloes pulling a heavy cart. Yama, the lord of death, sat in the carriage. When the other hell being became too weak to pull the carriage, Yama punished him by piercing him in the chest with a trident, causing him great agony, so he screamed.

The Buddha-to-be felt great compassion for this other hell being and pleaded with Yama, “Please let this sentient being go. Put his ropes over my head and I will pull your carriage myself.” Yama was enraged and also pierced Buddha with the trident, killing him. By virtue of the Buddha-to-be’s great act of compassion, his consciousness was transferred and he reincarnated in a god realm.

Think about it. It is no more logical to think “I am more important than this person” than it is to think “I’m more important than this insect.” Such a view has not one single logical reason to support it but is merely dictatorial and egotistical reasoning. An ant’s life may be of little consequence to us, but to the ant it is everything.

The self-cherishing view makes us tight with pride and willing to harm others who don’t obey our ego-based commands. How dangerous that is! Expel this self-important and self-cherishing mind that seeks happiness for ourselves above others. This mind has brought you all forms of dissatisfaction and denied you the happiness of this life, let alone liberation and enlightenment!

As ordinary people, we often complain about others abusing us, disrespecting us, and harming us. But if we practice exchanging self for others—the letting go of self-cherishing thought and cherishing others instead—these troubles simply stop. As we do this practice we will find we no longer receive harm from others and instead experience much peace, happiness, and success. Practice becomes easier and liberation and enlightenment become that much closer. Every moment of every day becomes one of contentment and happiness. Cherishing others is like a great holiday for the mind, a wonderful vacation from the oppressive self-cherishing thought.

If we do not realize that categories such as “good,” “bad,” “friend,” “enemy,” and “stranger” come from our own mental labels, we will see harm coming to us when somebody says words we interpret as unpleasant. In a flash we will see an enemy abusing us. Our suffering will become tangible.

Therefore self-grasping and self-cherishing are the real enemies to be kept out at all costs. As we overcome them, we will be destroying the creator of all problems, the delusions. If we peel back the layers of thought to find out why we repeatedly experience depression, disharmony, anger, attachment, dissatisfaction, jealousy, pride, and ill will, we will see that at the core of all our troubles is the thought “I am the most important; my happiness is paramount.” Numerous negative emotional states spring up because the “I” doesn’t get its way.

Anyone who successfully shields himself from the self-cherishing thought will find benefit in adverse situations, even the bad treatment and criticism of others. To such a person, these difficulties become meditations or Dharma challenges that are forceful ways to conquer the selfish mind. This kind of practitioner considers people who criticize him and treat him badly as the kindest and best of friends.

Such a person would offer the whole earth filled with diamonds to someone expressing criticism, seeing the situation in this way: “I have long followed the self-cherishing thought that brought endless sufferings of mind and body. I therefore know the painful lesson of being a slave to the self-cherishing thought. This critical sentient being is helping me by reminding me of that lesson. Together we are destroying my self-cherishing thought. How unbelievably kind this person is.”

When the practitioner thinks this way and sees the difficult person no longer as a harm-giver but as a helper in his progress, everything changes. Negative becomes positive.

"The essential way to practice exchanging self for others is to regard the suffering of others exactly as our own suffering and to help others as if they were ourselves."

The practice of exchanging self for others (tonglen) is meditating on taking the sufferings of sentient beings on ourselves and giving them every happiness. The elements of loving-kindness, great compassion, and the great will of altruism to carry the responsibility of helping sentient beings are infused into this practice.

As a preliminary to tonglen, first meditate on equanimity, equalizing oneself with others. We do this before starting the actual meditation of exchanging self for others. If we discriminate some sentient beings as close to us and some as distant from us, this causes bias, helping only some and not helping everyone. When we equalize all beings with ourselves, we cherish all beings as much as we cherish ourselves. It then becomes possible to work toward eliminating the sufferings of sentient beings by offering happiness to them equally.

This tonglen practice of exchanging self with others, of taking and giving, is very, very important. During this meditation, we visualize and mentally take on ourselves all the hardships of sentient beings with our in-breath, absorbing these into the self-cherishing, egotistical mind dwelling in our hearts and expunging that self-cherishing attitude. With our out-breath we visualize giving happiness to all sentient beings.

For example, if we are being scolded, instead of retaliating with abusive words we quietly and mentally take on ourselves the anger of the person scolding us, as well as the anger and sufferings of all sentient beings. We think, “May all their delusions and sufferings ripen on me right now and destroy my self-cherishing mind. May they receive wisdom and happiness.” In this way, we straightaway turn the anger directed at us on to the path to enlightenment.

Tonglen practice works similarly with situations of attachment, such as worry about our physical body if we are sick. During the practice, we visualize taking the sicknesses of all sentient beings on ourselves and we use that to destroy clinging to the “I.” We then send out thoughts of perfect health and joy to all sentient beings. Do this exchanging-of-self-for-others meditation repeatedly. It is only a mental practice, but a profound one.

Our enemy is not outside but in our hearts; it is within us. Our enemy is the selfish mind fueled by delusions that has colored our world black and brought countless lifetimes of suffering. Waste no time in completely destroying the selfish mind. If we do this practice of taking and giving, the real inner enemy has no chance of survival. This practice will allow us to gain the realization of bodhicitta in our hearts. It is unbelievably powerful. When we take on ourselves the anger and suffering results of number-less sentient beings, hell beings, hungry ghosts, animals, human beings, demigods, and gods, giving them only happiness in return, can you imagine the impact? It is magnificent. How much merit is generated!

It is the same with taking on the attachments of sentient beings and all of the attendant troublesome results. Whatever sufferings they experience, we visualize ourselves taking them on and using that to uproot our selfish mind. We then give away to others all merits and happiness, past, present, and future, including ultimate happiness. It is the main practice of exchanging self and others. While skies of merit are accumulated through this practice, it also accomplishes a great purification of our negativities. Numberless eons of negative karma from beginningless rebirths get purified through this practice. It is amazing.

Exchanging self for others is the best practice to do when you are dying. When death comes, just do tonglen. Wow. We will have incredible inner peace, happiness, and satisfaction from doing something so meaningful. We will die with bodhicitta. This is what His Holiness the Dalai Lama calls “self-supporting death.” Whenever a doctor says to us, “You have cancer,” the mind usually goes blank or sinks into panic. But those who understand and practice tonglen are unafraid and even feel ready for the challenge because they see it as an opportunity to “experience” cancer for others. Such people feel self-empowered, confident, brave, and able to benefit others. They are able to do this because they have a spiritual practice. They know how to do tonglen, the meditation on the exchange of self for others.

Therefore, if ever a doctor says we have cancer or some terrible disease, immediately stop and think how we can rely on the very special practice of exchanging self for others. This will enable us to make the best use of our sicknesses and our lives. Through this practice, we purify oceans of negative karmas and generate heaps of merit, which helps us in this life, at the time of death, and also in future lives. If we have cancer, then our remaining days can become a special and quick method to achieve enlightenment. Cancer becomes our own unique stick of dynamite, which if used together with tonglen is potent medicine to combat the elements and expedite our passage to enlightenment.

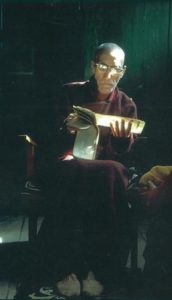

We can see the power of actualizing bodhicitta in the lives of two great Tibetan masters of the twentieth century. The late Kyabje Khunu Lama Rinpoche, a learned and pure practitioner of bodhicitta, was tutored by the great Buddhist masters in Tibet on philosophy and other types of knowledge. During the early days of Tibetans arriving in India after the Chinese takeover of their country, Khunu Lama Rinpoche lived like a yogi, dwelling with the Hindu sadhus in Varanasi along the Ganges River. One day, clothed like a sadhu—wrapped up in plain cloth and looking unwashed—Rinpoche went to a local Tibetan monastery to ask for a small room. The monks there did not recognize Rinpoche and said no room was available. Rinpoche slept outside on the bare ground, the way the beggars did.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama was visiting that place at the time and knew what was happening, so he went directly to where Khunu Lama Rinpoche was and requested teachings and commentary on the Bodhicaryavatara. Word quickly spread that a great bodhisattva was living there, and soon long lines of people gathered seeking advice from Rinpoche.

Kyabje Khunu Lama Rinpoche was able to recite by heart passages from any root text of the Buddha’s teachings and any of the commentaries. His mind was so robust and totally clear it was most amazing. His holy mind was like the entire Buddhist library.

I once went alone to Rinpoche to request a commentary on the Bodhicaryavatara. Rinpoche declined on that occasion but gave me the complete oral transmission of that text. Rinpoche then told me to translate the Bodhicaryavatara, even though he knew others had already translated it. “You translate,” Rinpoche said to me, advising me that before translating one must know the language and the subject well. I have not yet done the translation, but hope to do so sometime in the future.

I once attended teachings by Rinpoche that went on for a whole day with no break. Rinpoche then approached the wisdom chapter of the Bodhicaryavatara, an unbelievably precious teaching for one who seeks freedom from samsara. However, the minute Rinpoche started teachings on that chapter, I fell asleep. Until that moment I was wide awake. But when Rinpoche began the commentary, sleep overcame me. Some unbelievably bad and heavy negative karma from my past life must have caused that. Imagine—at the wisdom teaching that will bring liberation, I fell asleep!

After the teaching, Rinpoche gave some kambu, which are apricots in a bottle, that I think were from Ladakh. As he gave me the apricots, he said, “Subdue their minds.” I think that that was the last advice I received from Rinpoche. “You have the responsibility to subdue their minds.”

I have not yet subdued my own mind, so I do not know how to subdue the minds of others. But I try to offer advice when I am asked to give teachings.

Another great ascetic lama, Kari Rinpoche, spent his early days as a monk in a monastery in Sherka, close to the peak of a very high mountain. When I was still quite young and journeying to Tibet with others, we would stop and gaze up high into that isolated mountain monastery, which looked distant and tiny from where we stood. We wondered how we could get up there. Then we discovered a tiny uneven road spiraling around the mountain, constructed from rocks, wood, and patches of grass, that led up to the rocky mountain monastery.

When we arrived at the monastery, a community of about five hundred monks, we found everything very clean and neat. Kari Rinpoche had been asked to be the monastery administrator, which meant collecting barley from the villages and fields associated with that monastery and bartering for barley supplies. Barley was the main form of food for monks.

However, Kari Rinpoche was unskilled in business, so he completely failed in the task. Rinpoche said this failure was a profound lesson to him. By failing in business, he gained insight into samsara, which helped him generate renunciation. From that time, he committed himself to studying and meditating on the Dharma, doing extensive practices.

When traveling in Tibet one can see numerous mountains dotted with caves that were often used as hermitages by meditators who would spend years, sometimes their entire lives, meditating on the Dharma. Kari Rinpoche lived in such a hermitage for many years and never went outside. For sustenance, he relied on the chu-len practice of taking the essence of flowers, plants, and even stones, and transforming it into tiny mud pills that served as food. This reduces food preparation time. Just one pill suffices for the day, making the mind clear and enabling one to easily achieve the nine levels of the calm-abiding meditation.

Kari Rinpoche accomplished the renunciation of samsara and gained the realizations of bodhicitta and emptiness, after which he had clairvoyance and could tell the future. If you met this lama you did not have to ask your question. He could tell you what you were about to ask. He would know your intentions and your plans. He would offer you the advice you needed to fulfill your plans. His heart was filled with bodhicitta.

Kari Rinpoche was much sought after by people seeking prayers for help in daily life problems. He also offered prayers for those who had died, to liberate them from the lower realms or to prevent them from being reborn in the lower realms. This ascetic lama lived simply and kept nothing. He used any offerings he received to take care of the monks and nuns and whoever needed it. Due to the power of his bodhicitta, everything about him—his body and even his robes—became holy relics. When the time came for Rinpoche to take on the aspect of illness, he would sometimes vomit blood. His disciples would mix that with tsampa (roasted barley flour) and create small medicinal pills with extraordinary healing power.

Whenever we visited him when he seemed to be sick, and brought him news of Dharma teaching or something good happening in the world or for Tibetans, Rinpoche would immediately take on the aspect of recovery. Every part of Rinpoche carried blessings. These are just a few of the many results of actualizing bodhicitta.

| There are no products in your cart. |