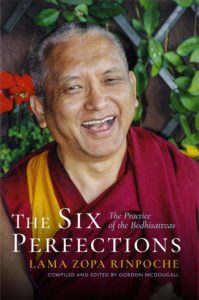

Lama Zopa Rinpoche is one of the most internationally renowned masters of Tibetan Buddhism, working and teaching ceaselessly on almost every continent. He is also the spiritual director and cofounder of the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition (FPMT).

The following is an excerpt from his book The Six Perfections.

HOW TO DEVELOP PERSEVERANCE

Great strength of will is needed even for worldly ends. Dictators have incredible determination and focus as they plot to invade and conquer other countries. Even if it takes them their entire lives, they realize their desire to destroy the other countries’ defenses and take them over, using every resource they have. Hitler, for example, was a person of great determination. Look at the great destruction he caused to the countries in Europe. He could not have done this if he thought it was all too big for him to accomplish.

If strong, sustained energy is necessary for worldly pursuits, then there is no question it is needed for practicing the Dharma. We need the determination that we will work tirelessly, no matter how long it takes. If we do have such a resolve, we won’t have to wait a hundred thousand eons. There are various methods that will free us from samsara very quickly, in three lifetimes or even in one. It depends on us putting sustained and strong energy into destroying our delusions, which is why the perfection of perseverance is so important.

Developing perseverance means overcoming the various forms of laziness, which are generally listed as three:

-

-

- The laziness of procrastination

- The laziness of being attached to worldly affairs

- The laziness of discouragement and low self-worth

-

Of this Shantideva said,

What are the adversaries of fortitude?

They are: indolence, a fondness for evil, despondency, and self-deprecation.

In addition, there are qualities we need to develop, which the texts usually list as these:

-

-

- aspiration

- unwavering resolve

- joy

- correct application

-

1. Overcoming the Laziness of Procrastination

When I was studying for my US passport, I had to learn about American history, about how the US freed itself from British control and about how people fought for the end of slavery. I’m afraid I made a complete mess of it, getting Pearl Harbor confused with the Civil War and not knowing what the Stars and Stripes was. One person who struck me as amazing was Martin Luther King Jr., who worked so hard for the rights of black people in the US. But as difficult were the fights to end slavery, for equal rights, and for women’s liberation, none of them are anywhere near as difficult or as urgent as the fight to be free from the dictatorship of the self-cherishing mind.

Under the yoke of the dictator—our self-cherishing—and controlled by his generals—the three poisons—we are fighting for our freedom. We must escape, and so we must use every means at our disposal. Because at present we have this perfect human rebirth, it is vital we don’t waste a moment of it; we must use every moment to develop bodhichitta. And yet we find it so hard to even pick up a Dharma book!

Under the dictatorship of the self-cherishing mind, we have made ourselves slaves to its derivatives: ignorance, attachment, and anger, and the other disturbing emotions. From beginningless lives we have been under their control, completely misunderstanding what freedom is. We have mistakenly thought they were a means for gaining freedom, and so we have followed them and enslaved ourselves to them. We cry out, “I want to be myself!” and yet we follow our self-cherishing as it leads us from one problem to the next. Our worries and fears are unending. As soon as one ends, the next begins. It’s the same thing again and again, like always opening a new box and finding the same things inside: relationship problems, work problems, and on and on. We think we are giving ourselves freedom by following the ego, but actually we are just working for our delusions — we are slaves to their dictates. Whatever our delusions want, we give in to them. With this totally wrong understanding, we force ourselves to suffer in samsara, just as we have from beginningless time. We have no energy for anything other than working for our delusions. We might be very active but this is laziness.

As Shantideva said,

Indolence develops when, out of inertia,

or due to a taste for pleasure, or due to mental torpor,

or because one craves for the comforts of a soft pillow,

one is not sensitive to the sufferings of transmigration.

At present we find it hard to find the time to meditate or study any Dharma. To even chant a mantra seems a chore. On the other hand, we have great energy for watching television or going to parties, or just staying in bed. When we understand how attachment to worldly pleasures, to the eight worldly dharmas, is trapping us, we can learn how real happiness lies in virtue. Then, when we have joy in virtue, we can turn our life around from nonvirtue to virtue.

Later in the chapter Shantideva said,

You have obtained this human condition,

which is like a raft — cross then the river of suffering.

You fool, this is no time for sleep,

you will not find this craft easily again.

The “raft” means this perfect human rebirth, the raft we use to cross the suffering of samsara and attain enlightenment. Because of its rarity and preciousness, and because it can be lost at any moment, while we have it we must not waste a moment; we must not sleep. That doesn’t mean we don’t sleep at all. By “sleep” Shantideva means letting our vigilance waver, lapsing back into nonvirtuous actions, and wasting this precious chance we now have.

"When we understand how attachment to worldly pleasures, to the eight worldly dharmas, is trapping us, we can learn how real happiness lies in virtue."

Of course, if we are attached to our bed then maybe Shantideva does mean sleep in that way. Maybe in that case we should follow the example of the monks and nuns in the big Tibetan monasteries and nunneries who often get up at three or four o’clock in the morning and do their prayers before a full day of study, pujas, and debate that very often doesn’t finish until very late at night. They survive on a few hours’ sleep each day because their minds are so energized with virtue, unlike we worldly people who need half the day to recover from the nonvirtuous activities that take up the other half.

Each second of this perfect human rebirth is more precious than skies filled with wish-granting jewels. Using this perfect human rebirth, within one second we can attain the three great meanings: a better future rebirth, liberation, and enlightenment. It gives us the most precious jewel of bodhichitta, which means we can fulfill our full potential and become a buddha in order to best serve others. Even if we don’t have a dollar to our name, even if we are not sure where tonight’s meal will come from, we are richer than a person possessing billions of diamonds and mountains of gold or even skies of wish-granting jewels.

We have this human body endowed with its eight freedoms and ten richnesses, and because of that we can use it as a boat to cross the ocean of samsara to the other side, to reach the end of suffering and its causes. We can use this boat to cease not just the gross defilements that block us from liberation from suffering but also the subtle defilements that block us from full enlightenment. Therefore, while we have this boat, we must use it.

In chapter 4 of A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, the chapter on conscientiousness, Shantideva showed us how rare obtaining such a human rebirth is—as rare as a blind turtle putting its neck through a golden ring floating on the ocean when it surfaces once every hundred years. Unless we take this precious opportunity now, the Lord of Death will come and our work will never be completed.

I remember the second pilgrimage I made to Tibet. Very near the birthplace of Lama Yeshe we came across a truck filled with thornbushes with a calf stuffed in one corner. It had big, terrified eyes, and we all knew it was on its way to the butcher. Knowing this was the calf’s fate, we stopped the driver and bought it.

When cows reach the slaughterhouse, as they are roughly pulled from the trucks by ropes through the rings in their noses and dragged to the slaughter yard, they pull back, instinctively fearing what will happen. The butcher then kills them with an axe or a big knife.

If they had human bodies, they could plead for their lives in billions of words; they could pay whatever bribe was demanded; they could do all sorts of things to escape. But they cannot communicate, and so, no matter how much fear they have, there is nothing they can do. They must wait to be slaughtered to become food for human beings.

They have all been human beings like us in numberless past lives but because they were unable to transform their minds by practicing the Dharma, they were forced to transmigrate into animal bodies and so suffer this result.

We have all sorts of karma, virtuous and nonvirtuous, on our mental continuum, collected since beginningless time. If we check to see how much of each kind of karma we accumulate in one day, can we truthfully say there is more virtuous than nonvirtuous? What actions, no matter how small, were done with the attachment clinging to this life? What actions were done with a bodhichitta motivation? Or with the right view or renunciation? What was the motivation for eating our breakfast? If it was attachment to this life, then each bite was nonvirtue, the cause of suffering; if it was renunciation, right view, or bodhichitta, then each bite was virtue, the cause of happiness. In the same way, when we check the motivation for going to work, for shopping, for sleeping—for all the many actions we do in one day—we can see if we are creating more virtuous or more nonvirtuous karma.

This is the choice we face every second of our life. Whatever we do can be virtuous or nonvirtuous, it can be Dharma or non-Dharma, it can be the cause for future happiness or future suffering. And so whatever we do can lead us to the fortunate upper realms or to the utter misery of the lower realms. This is why we must be so mindful of everything we do. If we are not careful with all our actions of body, speech, and mind, then the habitual nonvirtuous minds can take over, and we can do things that harm ourselves and others and plant the seeds for countless rebirths in the lower realms.

"Each second of this perfect human rebirth is more precious than skies filled with wish-granting jewels."

Reflecting on Impermanence Generates Perseverance

In one of the sutras it says that when a king dies, he leaves behind his palaces, his wealth, his wives, and his luxury; when a beggar dies, he leaves behind his walking stick. No matter how different their lifestyles were, they are both completely equal in death in what they can take with them—nothing. Like pulling a hair from butter, where not one atom of butter comes with the hair, at death our mind leaves our body and all our possessions and takes another body. The only thing we take with us is our accumulation of karmic imprints, both positive and negative.

When we die with attachment, we are terrified of losing everything, suddenly seeing all these things we have clung to being taken from us. In this state, we leave this life and go to the next. There is a popular saying:

You cannot be sure which will come first,

Tomorrow or the next life,

Therefore, do not put effort into tomorrow’s plans

But instead it is worthwhile to attend to the next life.

We leave everything behind when we die, even our body, this thing we cherish above all else. At present we treasure our friends, seeing them as sources of our happiness, but when we die they can do nothing to help us. They cannot share our suffering in the slightest. Furthermore, our attachment to them becomes a huge hindrance to our peaceful death. And so even if we have been with them all our life, at death they become capable of bringing us great harm.

Nothing is definite in samsara. As the Buddha said,

Everything together falls apart;

everything rising up collapses;

every meeting ends in parting;

every life ends in death.

There is the story of the four people who craved four different things. There was the king who craved power, the trader who craved possessions, the person who craved friends, and the person who craved a long life. The king was unable to hold on to his power and became powerless and miserable; the trader lost every possession; the person who craved friends was completely separated from them; and the person who craved a long life died young. Whatever we cling to we are bound to lose.

When we see this, we realize that we should not postpone our Dharma practice. We might wake up one day thinking we will live for a long time—and we will be dead before that day finishes. Or perhaps we will still be alive tomorrow. Who knows? The only guarantee is that we will die. Without that certainty, will we have the strength to go against our habitual laziness?

The great yogi Milarepa is a wonderful example of perseverance. Through reflecting on impermanence and death he found the courage to withstand incredible hardships in order to practice the Dharma, including living in a cave with nothing but a cooking pot and nettles to eat. Later on, he was able to control the four elements, meaning nothing could affect his health, but in the beginning he had to overcome the sufferings of heat, cold, hunger, and great discomfort in order to meditate. He said,

I fled to the mountains because I feared death.

I have realized emptiness, the mind’s primordial state.

Were I to die now, I have no fear.

Reflecting well on impermanence and death gives us the perseverance we need to withstand any hardship we encounter without fear. While we cling to samsara we fear so many things, but when we deeply understand the impermanence of all things, including our own life, we can overcome the cycle of death and rebirth. Rather than the sort of perseverance that makes us pursue what is meaningless, here, with the courage gained from the reflection on impermanence and death, we have the power and determination to overcome our delusions and only do what is meaningful in our life.

"The only guarantee is that we will die. Without that certainty, will we have the strength to go against our habitual laziness?"

The six perfections are the actions of the bodhisattvas—holy beings who have transcended selfless concerns. But they’re also skills we can and should develop right now, in our messy, ordinary lives.

The six perfections are the actions of the bodhisattvas—holy beings who have transcended selfless concerns. But they’re also skills we can and should develop right now, in our messy, ordinary lives.

In this clear, comprehensive guide to the backbone of Mahayana Buddhist practice, Lama Zopa Rinpoche walks us through each of the six perfections: charity, morality, patience, perseverance, concentration, and wisdom.

As he carefully describes each perfection, he not only reveals the depth of its meaning and how it intertwines with each other perfection, but he also explains how to practice it fully in our everyday lives—offering concrete ways for us to be more generous, more patient, more wise. With the guidance he gives us, we can progress in our practice of the perfections until we, like the bodhisattvas, learn to cherish others above ourselves.

| There are no products in your cart. |