The following is an excerpt from Courageous Compassion by His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Ven. Thubten Chodron, the newest volume in the Library of Wisdom and Compassion series.

All of us appreciate others’ kindness and compassion. Even before we came out of our mother’s womb, we have been the recipients of others’ kindness. Although being on the receiving end of compassion mollifies our anxiety and suffering, being compassionate toward others brings even more joy and feelings of well-being. This is what the eighth-century Indian sage Śāntideva meant when he said (BCA 8:129–30):

Whatever joy there is in this world

all comes from desiring others to be happy,

and whatever suffering there is in this world

all comes from desiring myself to be happy.

What need is there to say much more?

The childish work for their own benefit,

the buddhas work for the benefit of others.

Just look at the difference between them!

We need to learn methods to release our self-centeredness and cultivate genuine love and compassion for others. This does not entail feeling guilty when we are happy or sacrificing our own well-being, but simply recognizing that our self-centeredness is the cause of our suffering and cherishing others is the cause of the happiness of both self and others. In Praise of Great Compassion explains the two methods for doing so: the seven cause-and-effect instructions and equalizing and exchanging self and others. Now we’ll look at the activities that bodhisattvas engage in with compassion and wisdom to benefit the world.

Introduction to the Bodhisattva Perfections

We may not yet be bodhisattvas, but we can certainly engage in the same activities they do. In the process, we can continue and boost the intensity of our love and compassion.

Bodhisattvas train in bodhicitta for eons, so do not think that having one intense feeling of bodhicitta or reciting the words of aspiring bodhicitta is all there is to it. In Engaging in the Bodhisattvas’ Deeds, the first two chapters lead us in cultivating bodhicitta, and the third chapter contains the method for taking the bodhisattva vow. The other seven chapters describe the practices of bodhisattvas, training in the six perfections. Although these bear the names of familiar activities—generosity, ethical conduct, and so forth—now they are called “perfections” because they are done with the motivation of bodhicitta that aims at buddhahood, the state of complete and perfect wisdom and compassion.

As you progress through the bodhisattva paths and grounds, you will deepen and expand your bodhicitta continuously, as indicated in the twenty-two types of bodhicitta mentioned in the Ornament of Clear Realizations. With joy make effort to understand bodhicitta and the bodhisattva path, and endeavor to transform your mind into these. Avoid conceit and cutting corners; in spiritual practice there is no way to ignore important points and still gain realizations. Cultivate fortitude, courage, and the determination to be willing to fulfill the two collections of merit and wisdom over many years, lifetimes, and eons. The result of buddhahood will be more than you can conceive of at this moment.

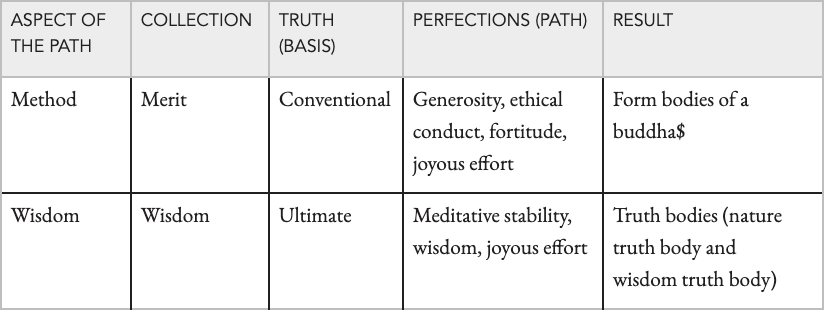

The Two Collections of Merit and Wisdom

Bodhicitta is a primary mind conjoined with two aspirations. The first is to work for the well-being of all sentient beings, the second is to attain full awakening in order to do so most effectively. Once you have generated bodhicitta and are determined to attain buddhahood, you’ll want to accumulate all the appropriate causes and conditions that will bring it about. These are subsumed in the collection of merit (puṇyasaṃbhāra) and the collection of wisdom ( jñānasaṃbhāra). The collection of merit is the method or skillful means aspect of the bodhisattva path that concerns conventional truths such as other living beings; the collection of wisdom is the wisdom aspect of the bodhisattva path that focuses on the ultimate truth, emptiness. When completed, the two collections lead to the form body and truth body of a buddha. In Sixty Stanzas (Yuktiṣaṣṭikā) Nāgārjuna summarizes these two principal causes:

Through this virtue, may all beings complete

the collections of merit and wisdom.

May they attain the two sublime buddha bodies

resulting from merit and wisdom.

TWO ASPECTS, TWO COLLECTIONS, TWO TRUTHS, PERFECTIONS, AND RESULTS

Note: There are various ways of categorizing the six perfections by way of method and wisdom. In another way, the first five perfections are included in the method.

The collection of merit consists of virtuous actions motivated by bodhicitta. The collection of merit includes mental states, mental factors, and karmic seeds related to these virtuous actions. It deals with conventional truths, such as sentient beings, gifts, precepts, and so forth. To fulfill it, bodhisattvas practice the perfections of generosity, ethical conduct, and fortitude, as well as all other virtuous actions such as those done with love and compassion, prostrating, making offerings, and meditating on the defects of saṃsāra.

The collection of wisdom is a Mahāyāna pristine knower that realizes emptiness. It consists of learning, contemplating, and meditating on the ultimate nature of persons and phenomena that is supported by bodhicitta, and includes both inferential reliable cognizers of emptiness that are free from the two extremes of absolutism and nihilism and āryas’ meditative equipoise on emptiness. The collection of wisdom is not necessarily a union of serenity and insight, but being a Mahāyāna exalted knower, it must be conjoined with actual bodhicitta and bear the result of buddhahood.

The collection of merit is primarily responsible for bringing about a buddha’s form bodies (rūpakāya), and the collection of wisdom is primarily responsible for bringing about a buddha’s truth bodies (dharmakāya). The word “primarily” is significant because each collection alone cannot bring about either of the buddha bodies. Both collections are necessary to attain both the form bodies and the truth bodies. (Here “body” means a corpus of qualities, not a physical body.) Bodhisattvas fulfill their own purpose by gaining the buddhas’ truth bodies and omniscient minds. They fulfill others’ purpose by manifesting in buddhas’ countless form bodies through which they benefit, teach, and guide sentient beings.

With bodhicitta as their motivation, bodhisattvas delight in creating the cause for buddhahood by practicing the perfections. Practices and activities that comprise the collections of merit and wisdom become perfections because they are conjoined with actual bodhicitta, which differentiates them from the practices of merit and wisdom cultivated by śrāvakas and solitary realizers. Although śrāvakas and solitary realizers collect merit and wisdom, they are not the fully qualified collections of merit and wisdom and are thus considered secondary collections. Because solitary realizers’ progress in merit and wisdom is superior to that of śrāvakas, some solitary realizers are able to become arhats without depending on hearing a master’s teaching during their last lifetime in saṃsāra.

Likewise, bodhisattva-aspirants who have not yet generated actual bodhicitta and entered the Mahāyāna path of accumulation create merit and enhance their wisdom, but their practices are called “similitudes” of the two collections and are not fully qualified collections. However, people who aspire to enter the bodhisattva path plant the seeds to be able to do the actual collections later.

Our virtuous actions accompanied by a strong wish for a good rebirth act as a cause for the places, bodies, and possessions associated with fortunate rebirths. Those accompanied by the determination to be free from cyclic existence are similitudes of the collections and lead to liberation. Only when our virtuous actions are accompanied by bodhicitta do they constitute the actual collections. Practitioners of the Perfection Vehicle build up the actual collections over three countless great eons on the bodhisattva path. The first eon of collecting merit and wisdom is done on the path of accumulation and the path of preparation; the second eon is fulfilled on the first seven of the ten bodhisattva grounds that span the path of seeing and part of the path of meditation; the third eon is done on the last three of the ten bodhisattva grounds called the “three pure bodhisattva grounds”—the eighth, ninth, and tenth. Bodhisattvas who follow the Vajrayāna fulfill the two collections more quickly due to the special practice of deity yoga that combines method and wisdom into one consciousness.

The method side entails cultivating an aspiring attitude—that is, we enhance our intentions to give, to not harm others, to remain calm in the face of suffering, and so on. With the practice of wisdom, we learn and contemplate the teachings on emptiness, bringing conviction and ascertainment that all persons and phenomena lack inherent existence. This wisdom complements and completes the practices on the method side of the path. Similarly, our virtuous actions of the method aspect of the path enhance wisdom by purifying the mind and enriching it with merit, which increases the power of wisdom. Method practices help the understanding of emptiness to arise when it hasn’t occurred, and when it has, merit enables wisdom to increase, deepen, and become a more powerful antidote to the afflictive and cognitive obscurations. Ultimately, however, it is wisdom that determines progress on the path because advancing from one bodhisattva ground to the next occurs during meditative equipoise on emptiness.

The Six Perfections

Cultivating contrived bodhicitta through effort is virtuous and auspicious; it paves the way to generate uncontrived bodhicitta, which entails engaging in the bodhisattvas’ deeds. These deeds can be subsumed in the six perfections—generosity (dāna, dāna), ethical conduct (śīla, sīla), fortitude (kṣānti, khanti), joyous effort (vīrya, viriya), concentration (dhyāna, jhāna), and wisdom (prajñā, paññā). The sixth perfection, wisdom, can be further expanded into four, making ten perfections—the first six, plus skillful means (upāya), unshakable resolve (praṇidhāna, panidhāna), power (bala), and pristine wisdom ( jñāna, ñāṇa). To ripen others’ minds, we train in the four ways of gathering disciples—generosity, teaching the Dharma according to the capacity of the disciples, encouraging them to practice, and embodying the Dharma in our life. These four can be included in the six perfections, so the six are said to be the main bodhisattva practices to ripen both our own mind and the minds of others.

You may wonder: From the beginning, the lamrim teachings encourage us to be generous and ethical, to have fortitude and practice with joyous effort, and to develop meditative stability and wisdom. Why, then, are these six practices explained only now? Also, practitioners of all three vehicles cultivate these qualities. Why are they explained now as unique Mahāyāna practices?

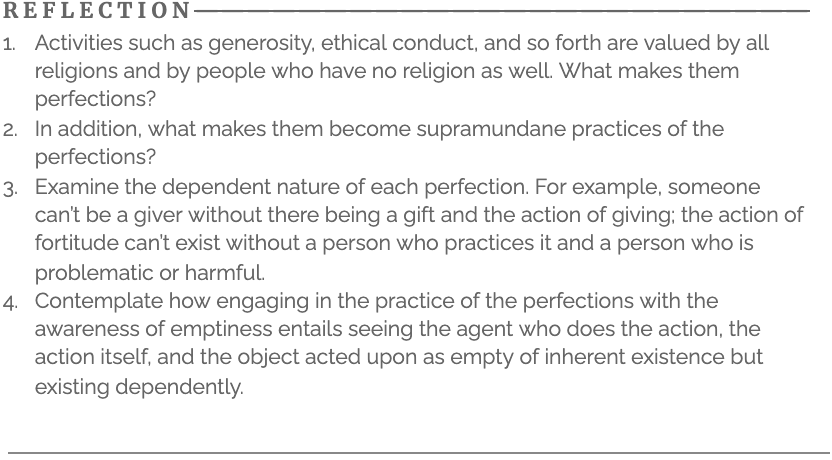

Let’s use generosity as an example. It is practiced not only in all Buddhist traditions but also in all religions. People who are not interested in any religion but value kindness and compassion also practice generosity. A difference exists, however, between the mere practice of generosity and the perfection of generosity. The perfection of generosity is not simply an absence of miserliness when giving or a casual wish to share things. Nor is it being generous with the motivation to be rich in future lives. Rather, it is giving done with the aspiration to become a buddha in order to benefit all beings most effectively.

In addition to being motivated by bodhicitta, the perfection of generosity is sealed by the wisdom of emptiness. That is, when giving, we reflect on the ultimate nature of the giver, the gift, the recipient, and the action of giving. All of them are empty of inherent existence but exist dependent on one another. Through this reflection, any attachment or misconceptions that could arise from generosity are purified. Based on bodhicitta and assisted by the wisdom of emptiness, the perfection of generosity encompasses both the method and wisdom sides of the path and is enriched by them.

The term perfection—pāramitā in Sanskrit and pāramī in Pāli—has the meaning of going beyond the end and reaching perfection or fulfillment. The Tibetan term pha rol tu phyin pa means to go beyond to the other shore. These practices take us beyond saṃsāra to the freedom of full awakening where both obscurations have been eliminated and all good qualities have been developed limitlessly. “Go beyond” connotes the goal—full awakening, or the Mahāyāna path of no-more-learning—as well as the method for arriving at that goal—the six perfections done by those on the learning paths. Motivated by bodhicitta and refined with meditation on emptiness, these practices take us beyond both saṃsāra and the pacification of saṃsāra that is an arhat’s nirvāṇa. For example, bodhisattvas who conjoin their actions of giving with unpolluted wisdom see the giver, the object given, the recipient, and the action of giving as empty of inherent existence. Because their wisdom is supramundane, the generous actions conjoined with it lead them beyond saṃsāra. Ārya bodhisattvas, who have achieved an extraordinary level of training in the six perfections, are objects of veneration and respect, for they both perceive ultimate truth directly and seek to benefit all beings.

Generosity and other perfections that are not conjoined with such wisdom are considered mundane because the agent, object, and action are seen as truly existent. To integrate the wisdoms of emptiness and dependent arising into your practice of generosity, reflect that you as the giver (agent), the gift that is given (object), the recipient, and the action of giving do not exist from their own side; they exist dependent on one another. A person does not become a giver unless there is a gift, recipient, and action of giving. Flowers do not become a gift unless there is a person giving them and one receiving them. Seeing all the elements of generosity as appearing but empty makes our generosity extremely powerful, transforming it into the supramundane practice of the perfection of generosity.

Similarly, when purifying nonvirtue during your practice of ethical conduct, contemplate that prostrations and mantra recitation, for example, do not have inherent power to purify destructive karma. Their ability to do so arises dependent on the strength of your regret, your motivation, the depth of your concentration, and faith in the Three Jewels. Both prostrations and the seeds of destructive karma they destroy are dependent arisings; they exist nominally, by being merely imputed by term and concept.

How can purification occur if both the seeds of destructive actions and the purification practices lack inherent nature and exist like illusions? It is analogous to soldiers in a hologram destroying an arsenal in a hologram. The scene and its figures appear, but none of them exists in the way they appear. If seeds of destructive karmas had their own intrinsic nature, independent of all other things, nothing could affect them and they would be unchangeable. But because they do not exist under their own power, they can be altered and removed by purification practices that alter the factors upon which they depend. This contemplation differentiates the perfection of generosity and so forth from the same actions done by others. The presence of the bodhicitta motivation differentiates the perfection of generosity from the giving done by śrāvakas and solitary realizers.

Each of the perfections is a state of mind, not a set of external behaviors. When certain mental qualities are cultivated, they undoubtedly affect a person’s behavior. However, external behavior may or may not be indicative of particular mental qualities. For example, a person may outwardly appear generous while her internal motivation is to manipulate the recipient. Likewise, we shouldn’t think that bodhisattvas always give extravagantly. A practitioner may have deep bodhicitta and a strong aspiration to give but, due to lack of resources, only give a small amount. Practitioners of the six perfections are extremely humble. They hide their realizations and do not seek fame or recognition.

"We may not yet be bodhisattvas, but we can certainly engage in the same activities they do."

The Basis, Nature, Necessity, and Function of the Six Perfections

Maitreya’s Ornament of the Mahāyāna Sūtras (Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra) describes the six perfections in detail. The following explanation is taken predominantly from that text.

The Basis: Who Engages in the Perfections?

Those who are a suitable basis for these practices have awakened their Mahāyāna disposition—that is, they have great compassion, deep appreciation, and fortitude for the Mahāyāna Dharma. They rely on a qualified Mahāyāna spiritual mentor and receive extensive teachings on the Mahāyāna texts that teach the six perfections. In that way, they learn what the bodhisattva practices are and how to do them correctly. These practitioners are not satisfied with intellectual knowledge: they reflect and meditate on these teachings to collect both merit and wisdom and they engage in the practice of the perfections at every opportunity. The Mahāyāna disposition is awakened before a practitioner generates bodhicitta. When this disposition is nourished and developed, it will lead a practitioner to generate uncontrived bodhicitta and enter the bodhisattva path.

Nature: What Constitutes Each Practice?

Knowing what constitutes each perfection gives us the ability to practice it more carefully.

- Generosity is physical, verbal, and mental actions based on a kind thought and the willingness to give.

- Ethical conduct is restraining from nonvirtue, such as the seven nonvirtues of body and speech and the three nonvirtues of mind that motivate them, as well as other negativities.3

- Fortitude is the ability to remain calm and undisturbed in the face of harm from others, physical or mental suffering, and difficulties in developing certitude about the Dharma.

- Joyous effort is delight in virtues such as accomplishing the purposes of self and others by creating the causes to attain the truth bodies and form bodies of a buddha.

- Meditative stability is the ability to remain fixed on a constructive focal object without distraction.

- Wisdom is the ability to distinguish conventional and ultimate truths as well as to discern what to practice and what to abandon on the path.

In the Precious Garland, Nāgārjuna speaks of the six perfections and their corresponding results. He adds a seventh factor, compassion, because it underlies the motivation to engage in the six perfections (RA 435–37):

In short, the good qualities

that a bodhisattva should develop are

generosity, ethical conduct, fortitude, joyous effort,

meditative stability, wisdom, compassion, and so on.

Giving is to give away one’s wealth;

ethical conduct is to endeavor to help others;

fortitude is the abandonment of anger;

joyous effort is enthusiasm for virtue.

Meditative stability is unafflicted one-pointedness;

wisdom is ascertainment of the meaning of the truths;

compassion is a state of mind that savors

only loving-kindness for all sentient beings.

The Necessity and Function of the Perfections

The six perfections are necessary (1) to accomplish the welfare of other sentient beings, (2) to fulfill the aims of ourselves and others, and (3) to receive a precious human life in future rebirths so that we can continue to practice. These are explained below.

Accomplishing the Welfare of Other Sentient Beings

Our practice of each perfection functions to benefit sentient beings:

- By giving generously, we alleviate poverty and provide others with the basic necessities of life and other practical items as well as with things they enjoy.

- By living ethically, we refrain from harming them, thus easing their fear and pain.

- By being patient with others’ inconsiderate or harmful behavior, we avoid causing them either physical pain or the mental pain of guilt, remorse, and humiliation.

- With joyous effort, we continue to help others without laziness, resentment, or fatigue.

- With meditative stability, we gain the superknowledges, such as clairvoyance (the divine eye), and use them to benefit sentient beings.

- With wisdom, we are able to teach others so that they can actualize the wisdoms understanding conventional truths, ultimate truths, and how to benefit others. Through this we eliminate their doubts and lead them to awakening.

Fulfilling Our Own Aims

The last three perfections—joyous effort, meditative stability, and wisdom—are cultivated primarily to fulfill our own aims—that is, to spur us on the path to buddhahood. Wisdom realizing the ultimate truth directly eliminates our ignorance, afflictions, and polluted karma so that our mind can be transformed into a buddha’s omniscient mind. To develop this wisdom that is a union of serenity and insight, we need deep meditative stability that makes the mind pliant and able to meditate on a virtuous object for as long as desired. To develop meditative stability, joyous effort is important to overcome laziness and resistance to Dharma practice.

Fulfilling the Aims of Others

The first three perfections primarily help to fulfill others’ aims. These center around ethical conduct. If we are attached to our possessions, body, and friends and relatives, we will harm others to procure and protect them. By cultivating generosity, our attachment will decrease and we will not harm others to get what we want. If our anger is strong, it will move us to cause others pain and misery. By cultivating fortitude, we will abandon harming others. Not only will they not feel pain from our harm but they will also not create more destructive karma by retaliating. Furthermore, they could be inspired by our fortitude and become more interested in learning how to subdue their own anger.

The first three perfections benefit others in another way as well. Through our being generous, they receive what they need and desire. Generosity also attracts others to us, so that we can teach them the Dharma and guide them on the path to awakening.

Even though we may practice generosity, harming others will damage our virtuous actions and diminish any benefit we could provide others. By living ethically, we stop injuring others physically and mentally. In addition, our ethical conduct draws others to us because they know we are trustworthy. This enables us to benefit them even more.

To practice generosity and ethical conduct well, fortitude is indispensable. If others are not grateful after we give them something, we might become angry and retaliate. That would harm them and violate our own ethical conduct. By practicing the fortitude of not retaliating, our ethical conduct will be stable and we will not become discouraged by others’ lack of gratitude when we are generous and kind to them. Fortitude with students, benefactors, and others we encounter in society is necessary because if we are irascible, they will avoid us—depriving us of the opportunity to benefit them.

Ensuring a Precious Human Life in the Future

Fulfilling the collections of merit and wisdom will take a long time. Thus it is essential to ensure that we obtain fortunate rebirths in which all the conducive circumstances for Dharma practice are present. If we are careless and fall to an unfortunate birth, we will not be able to help ourselves or practice the Dharma, let alone benefit others. To fulfill the purposes of self and others, a precious human life with excellent conditions is needed. Practicing the six perfections creates the causes to obtain this.

- Poverty creates difficulties in practicing the Dharma. Thus we need resources in future lives, and generosity creates the cause to obtain them.

- To make use of the resources, a human life is essential; ethical conduct is the principal cause of attaining an upper rebirth.

- Someone who ruminates with anger or loses their temper is not pleasant to be with and will lack good friends in the Dharma. Practicing fortitude creates the cause to have a pleasing appearance, good personality, and kind companions who encourage our Dharma practice and practice together with us.

- Being unable to follow through and complete projects is a hindrance to benefiting others. To be able to complete our virtuous projects in future lives and to be successful in all constructive activities we undertake, practicing joyous effort in this life is important. It creates the cause to have these abilities and to attract others to practice together with us in future lives.

- If our mind is filled with many afflictions in future lives, we will create great destructive karma. Having a stable and peaceful mind is important to maintain focus on what is important and not be distracted by uncontrolled thoughts and emotions. Practicing meditative stability in this life creates the cause for this.

- The ability to clearly discriminate between misleading teachers and those imparting the correct path is essential, as is the ability to discern what to practice and what to abandon on the path. Cultivating the wisdom that correctly understands the law of karma and its effects creates the cause to have such wisdom in future lives.

Engaging in all six perfections and reaping their results facilitates our Dharma practice in future lives. If the practice of even one perfection is weak or absent, our opportunity to progress on the bodhisattva path in future lives will be limited. For example, without the meditative stability that subdues the gross afflictions, our meditations on bodhicitta and emptiness will be weak; without wisdom, even if we have a good rebirth in the next life, we won’t have one after that because our ignorance will prevent us from creating the causes.

In short, Nāgārjuna sums up the temporal results of engaging in the six perfections that will facilitate our Dharma practice in future lives (RA 438–39):

From generosity comes wealth; from ethics happiness;

from fortitude comes a good appearance; from [effort in] virtue brilliance;

from meditative stability peace; from wisdom liberation;

compassion accomplishes all aims.

From the simultaneous

perfection of all seven,

one attains the sphere of inconceivable wisdom—

protector of the world.

Thinking about these teachings in relationship to our own lives will deepen our understanding and invigorate our Dharma practice. It is easy to be blasé about having the conditions to continue Dharma practice in future lives. However, imagining being born in circumstances that lack all the conducive conditions wakes us up to the need to create the causes to have them in future lives. Since those causes must be created now, our mind returns to the present with renewed vigor and interest in practice.

"People who aspire to enter the bodhisattva path plant the seeds to be able to do the actual collections later."

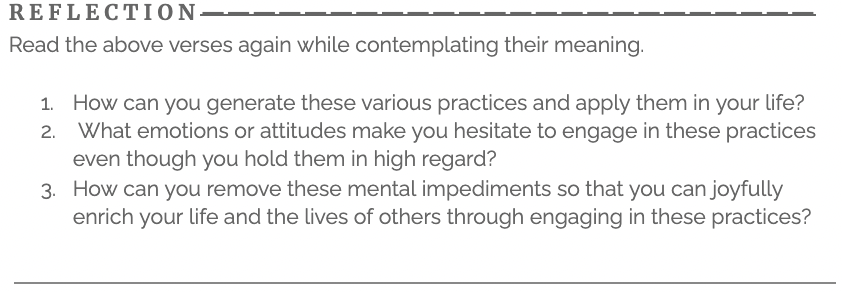

How the Six Perfections Relate to Other Practices

Although monastics and lay followers alike practice all six perfections, the first three—generosity, ethical conduct, and fortitude—are said to be easier for lay practitioners. In that context, generosity is giving material wealth and protection, ethical conduct is living in the five lay precepts and the bodhisattva precepts, and fortitude is the fortitude of gaining certitude about the Dharma, especially about the teachings on emptiness. The last three perfections—joyous effort, meditative stability, and wisdom—are likewise practiced by everyone but are said to be more pertinent to monastics.

Although we are encouraged to practice all six perfections as best as we can from the beginning, it is easier to cultivate and perfect them in their given order. Generosity precedes ethical conduct because attachment to possessions and greed to have more and better are obstacles to abandoning nonvirtuous actions. Ethical conduct is needed for fortitude because by practicing ethical conduct, it is easier to control afflictions and remain calm in the face of harm or suffering. Fortitude is needed to gain joyous effort because the internal calm that fortitude brings sustains joyous effort. Joyous effort is needed to develop meditative stability because meditative concentration does not come quickly and requires continuous effort over time. Meditative stability is essential for developing sharp, clear wisdom that penetrates the meaning of any topic, especially ultimate reality.

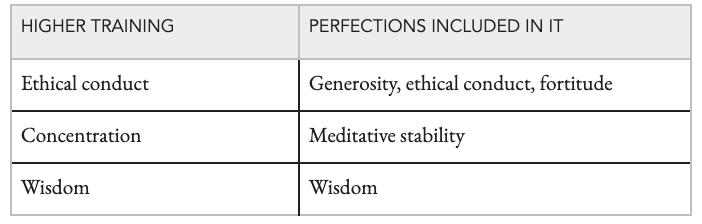

The six perfections comprise the two collections, as discussed above. They can also be included in the three higher trainings of bodhisattvas. Here generosity, ethical conduct, and fortitude are included in the higher training of ethical conduct; meditative stability pertains to the higher training of concentration; and wisdom is incorporated in the higher training of wisdom. Joyous effort is needed for all of them.

THE THREE HIGHER TRAININGS AND THEIR CORRESPONDING PERFECTIONS

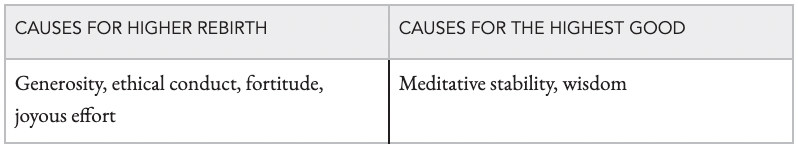

The six perfections also make up the two purposes of a practitioner: to obtain a higher rebirth and to actualize the highest good—liberation and full awakening. The first four perfections assist in attaining a higher rebirth. Meditative stability and wisdom are the keys to the highest good.

THE CAUSES FOR HIGHER REBIRTH AND THE HIGHEST GOOD

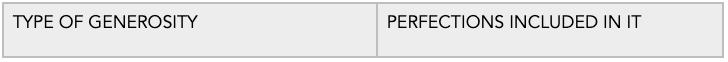

From another perspective the six perfections can be included in the three types of generosity. The perfection of generosity is the generosity of giving material possessions. Ethical conduct and fortitude are the generosity of fearlessness because by acting ethically we protect others from the fear of our harming them and by having fortitude we do not cause others pain by losing our temper. The perfections of meditative stability and wisdom are the generosity of Dharma because instructions on serenity and insight are the principal teachings to give to sentient beings when they are receptive vessels. Joyous effort is needed to complete all three types of generosity.

THE THREE TYPES OF GENEROSITY AND THEIR CORRESPONDING PERFECTIONS

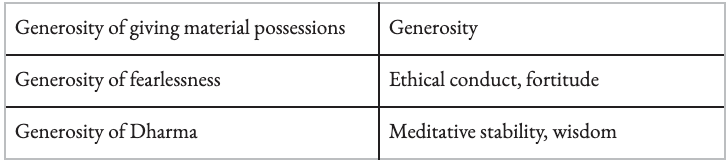

The six perfections are necessary to keep us on the path and to enable us to accomplish our heartfelt spiritual aims. Two factors inhibit us from embarking on the path: attachment to wealth and attachment to family and home. By sharing our resources, generosity lessens the first. By keeping monastic precepts, ethical conduct alleviates the second.

We may go beyond these two attachments but still abandon the spiritual journey as a result of two hindrances: the first is resentment for others’ bad behavior and their lack of appreciation and respect, the second is discouragement regarding the length of time needed and the depth of practice required to accomplish our aims. Fortitude counteracts the first by strengthening our ability to handle hardship. Joyous effort remedies the second by increasing our delight and enthusiasm for creating virtue. These two together soothe the mind and give us great confidence and perseverance to continue on the path no matter what.

We may continue to practice, but our virtue may go to waste and our efforts may bring negligible results due to two causes: distraction and mistaken intelligence. Distraction scatters the mind to sense objects, useless thoughts, and disturbing emotions, diminishing the force of our virtue. Meditative stability remedies this by keeping our attention focused on a virtuous object and enables us to penetrate the Buddha’s teachings and integrate their meaning in our mind. Mistaken intelligence inhibits comprehending and practicing the Buddha’s teachings correctly and could actively misunderstand the teachings and lead to activities that cause unfortunate rebirths. Wisdom prevents this by correctly ascertaining what is and is not the path, and in this way guides our body, speech, and mind in the right direction.

"By cultivating generosity, our attachment will decrease and we will not harm others to get what we want."

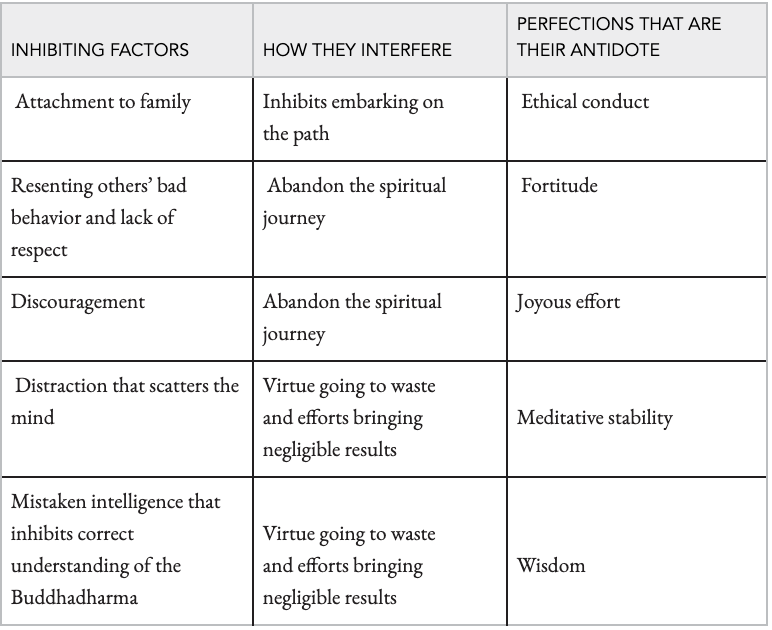

FACTORS INHIBITING THE ACCOMPLISHMENT OF SPIRITUAL GOALS AND THEIR ANTIDOTES

All six perfections can be included in the practice of each one. For example, giving even a glass of water—a small act of generosity—can be done with bodhicitta. The mental state is most important, and in this case it is the wish to give in order to accumulate merit to attain awakening for the sake of all sentient beings as well as to directly benefit the recipient.

Not harming others physically or verbally when getting the water and when giving it is ethical conduct. Refraining from a condescending attitude or rude behavior and eschewing harsh speech when offering also constitute ethical conduct. If the recipient harms us physically or verbally in return, remaining calm and not retaliating in response to their ingratitude is the practice of fortitude. Giving the water is done with joyous effort that takes delight in being generous. Stability of mind is necessary so that the mind does not get distracted while giving. Stability also maintains the bodhicitta motivation and prevents the mind from becoming polluted by afflictions while giving.

Prior to giving, wisdom is needed to know what, when, and how to give. While giving, contemplating the emptiness of the giver, gift, recipient, and action of giving cultivates wisdom. An early Mahāyāna sūtra, the Inquiry of Ugra (Ugraparipṛcchā), describes how this is done (IU 244):

When the householder bodhisattva sees someone in need, he will fulfill the cultivation of the six perfections:

- If as soon as the householder bodhisattva is asked for any object whatsoever, his mind no longer grasps at the object, in that way his cultivation of the perfection of generosity will be fulfilled.

- If he gives while relying on bodhicitta, in that way his cultivation of the perfection of ethical conduct will be fulfilled.

- If he gives while bringing to mind love toward those in need and not producing anger or animosity toward them, in that way his cultivation of the perfection of fortitude will be fulfilled.

- If he is not depressed due to a wavering mind that thinks “If I give this away, what will become of me?” in that way the perfection of joyous effort will be fulfilled.

- If one gives to someone in need and, after having given, is free from sorrow and regret, and moreover gives [these things] from the standpoint of bodhicitta and is delighted and joyful, happy, and pleased, in that way his cultivation of the perfection of meditative stability will be fulfilled.

- And if, when he has given, he does not imagine the phenomena [produced by his generosity] and does not hope for their maturation, and just as the wise do not settle down in [their belief in] any phenomena, just so he does not settle down [in them], and so he transforms them into supreme, full awakening—in that way his cultivation of the perfection of wisdom will be fulfilled.

While learning about the perfections, you may become discouraged, thinking that the practices are so difficult and you will never be able to do them. If this happens, instead of expecting yourself to be an expert when you are a beginner, accept your present level of abilities and continue to increase them in the future. The Buddha did not start off fully awakened and there was a time when he too found practicing the bodhisattva deeds very challenging. However, because causes bring their corresponding results, through steady practice you will be able to begin, continue, and complete the bodhisattvas’ practices. Ratnadasa said in Praise of Endless Qualities (Guṇapāryantastotra, CTB 201):

Those deeds which, when heard of, scare worldly [people],

and which you could not practice for a long time,

will in time become spontaneous for all familiar with them.

Those not so familiar find it hard to increase attainments.

Śāntideva agrees (BCA 6.14ab):

There is nothing whatsoever

that is not made easier through acquaintance.

Seeing that this is the case, let’s recall our buddha nature and transform our mind!

Courageous Compassion, the sixth volume of the Library of Wisdom and Compassion, continues the Dalai Lama’s teachings on the path to awakening. The previous volume, In Praise of Great Compassion, focused on opening our hearts with love and compassion for all living beings, and the present volume explains how to embody compassion and wisdom in our daily lives. Here we enter a fascinating exploration of bodhisattvas’ activities across multiple Buddhist traditions—Tibetan, Theravāda, and Chinese Buddhism.

Courageous Compassion, the sixth volume of the Library of Wisdom and Compassion, continues the Dalai Lama’s teachings on the path to awakening. The previous volume, In Praise of Great Compassion, focused on opening our hearts with love and compassion for all living beings, and the present volume explains how to embody compassion and wisdom in our daily lives. Here we enter a fascinating exploration of bodhisattvas’ activities across multiple Buddhist traditions—Tibetan, Theravāda, and Chinese Buddhism.

After explaining the ten perfections according to the Pāli and Sanskrit traditions, the Dalai Lama presents the sophisticated schema of the four paths and fruits for śrāvakas and solitary realizers and the five paths for bodhisattvas. Learning about the practices mastered by these exalted practitioners inspires us with knowledge of our minds’ potential. His Holiness also describes buddha bodies, what buddhas perceive, and buddhas’ awakening activities.

Courageous Compassion offers an in-depth look at bodhicitta, arhatship, and buddhahood that you can continuously refer to as you progress on the path to full awakening.

The Library of Wisdom and Compassion is a special multivolume series in which His Holiness the Dalai Lama shares the Buddha’s teachings on the complete path to full awakening that he himself has practiced his entire life. The topics are arranged especially for people seeking practical spiritual advice and are peppered with the Dalai Lama’s own unique outlook. Assisted by his long-term disciple, the American nun Thubten Chodron, the Dalai Lama sets the context for practicing the Buddha’s teachings in modern times and then unveils the path of wisdom and compassion that leads to a meaningful life and sense of personal fulfillment. This series is an important bridge from introductory to profound topics for those seeking an in-depth explanation from a contemporary perspective.

| There are no products in your cart. |