John Dunne holds the Distinguished Chair in Contemplative Humanities at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He received his PhD in Sanskrit and Tibetan studies from Harvard University.

The following is his introductory essay to Gross and Subtle Minds, Part 3 of Science and Philosophy in the Indian Buddhist Classics, Volume 2: The Mind.

A Tantric Perspective

The notion that consciousness occurs at various degrees of subtlety is found in many Indian traditions, and Buddhism is no exception. According to Buddhist theorists, subtle states can occur both naturally and as a result of contemplative practice, and while they can be harnessed to various purposes, they especially offer the opportunity to explore the nature of consciousness in forms that are not cluttered by the hubbub—or even the chaos—of a mind in the usual “gross” consciousness of everyday life.

Our authors begin with a well-known typology of consciousness in three contexts: awake, dreaming, and dreamless sleep, with dreamless sleep being the subtlest. They further note that, during the waking state, mental consciousness is subtler than sense consciousness: thinking of an apple is subtler than seeing one. These notions of the subtlety of consciousness are formulated from the theoretical standpoint assumed by most of this volume. But our authors begin to leave that standpoint behind when they move on to a discussion of the subtle levels of consciousness that transpire in the death process. This in turn quickly leads to this part’s main theme: the levels of consciousness as depicted in Buddhist tantric texts. To introduce this account of “gross and subtle minds,” I will thus focus on the tantric perspective, which shifts our exploration of the mind into a context quite unlike the other parts of this compendium.

Although the precise history of tantric practice in India is obscure, by the time Buddhism began to be established in Tibet in the eighth century, the dominant style of Buddhist practice in India was tantric. The term tantra refers to a genre of Buddhist literature that was said to be transmitted in secret to a select audience. These texts stand in distinction from the sūtras, discourses taught to a wide audience by Śākyamuni, the historical Buddha. Traditional accounts maintain that the tantras were also taught by the historical Buddha, although not in his ordinary form. Whatever one might say about the difficult question of authorship, from the time Buddhism first reached Tibet until the end of the thirteenth century, when the historically attested interchange between Tibetan and Indian Buddhists dwindled to the point of disappearance, tantric practice was indisputably at the center of all the Tibetan traditions, where the texts and practices fall under the rubric of the Vajrayāna, or “Diamond Vehicle.”

The Vajrayāna includes a strikingly wide array of texts and methods, but most are not relevant to understanding our authors’ discussion of gross and subtle minds. Instead, only two aspects of Vajrayāna theory require our attention. First, in relation to the subtlest level of consciousness, Vajrayāna theory proposes a nondual interpretation of the relationship between mind and body, such that the substance dualism assumed in other sections of this compendium does not apply. Second, Vajrayāna offers a set of techniques—perhaps even a “technology”—that manipulates the mind-body system in ways that are said to be especially effective in producing the transformations that are central to Buddhist practice. A brief look at this nondual account and the methods or technology that flow from it will help to clarify our authors’ discussion of gross and subtle minds.

“Wind” and Mind: A Nondual Perspective

In other parts of this volume, the general level of analysis adopted by our authors assumes what is often called substance dualism. From this perspective the mental and the physical are distinct because they are made of different kinds of “substances”—namely, material stuff and mental stuff. Importantly, even this dualistic account does not assume that mind can simply exist in complete independence of some type of embodiment. Instead, the mind stands in an interdependent relationship with its “basis” (Tib., rten), the physical body, which acts as a container or substratum within and through which mind functions. In the form of Buddhist tantra most relevant to our authors’ analysis, this relationship between mind and its basis moves beyond substance dualism by articulating a fundamental energy called wind (Tib., rlung; Skt., vāyu). In the first volume of this series, wind figures prominently as one of the four primary elements (Skt., mahābhūta) that constitute the physical world, where wind accounts for the basic lightness, mobility, and motility of physical entities. As tantric traditions emerge in India, however, wind takes on meanings that, connecting to developments in Indian medical theories, attribute to it a central role in the embodied mind, where this fundamental energy facilitates many capacities, including physical movement, cognitive processes, and consciousness itself.

Chapter 30 of the first volume in this series discusses in detail the most typical Tibetan account of the Vajrayāna model that presents wind as playing a key role in the functioning of the embodied mind. This Vajrayāna model involves an elaborate model of a “subtle body” featuring 72,000 channels—branching from three main channels—in which ten types of wind energy flow and where drops (Skt., bindu) or vital essences occur at key locations. Our authors’ detailed account of this complex, subtle physiology need not be reiterated here, except for one important point: in its subtlest state, known as the extremely subtle mind (Tib., shin tu phra ba’i sems), consciousness is indistinguishable from its basis, the extremely subtle wind (Tib., shin tu phra ba’i rlung). In other words, to adopt a typical metaphor, the subtlest level of consciousness is nothing other than the extremely subtle energy on which it is “mounted,” and that extremely subtle energy is nothing other than the extremely subtle consciousness that is its “rider.” Thus, while the mind-body distinction can be maintained at a coarse level, that distinction falls away at the subtlest level from the perspective of Vajrayāna theory. In their own discussion of this issue in the previous volume, our authors thus say that “at the subtlest level, given that wind and consciousness exist as a single entity, no differentiation can be made between the two in terms of their reality”. Clearly, we have arrived at a nondual account of the relation between mind and body, albeit one that presumes that the only “body” left is an extremely subtle form of energy. As it turns out, that particular mind-body configuration occurs reliably only at death, and that is precisely the main target of what we might call the technology of tantra.

"From this perspective the mental and the physical are distinct because they are made of different kinds of 'substances'—namely, material stuff and mental stuff."

The Technology of Tantra

Most of our authors’ discussion of gross and subtle minds focuses on a Vajrayāna tantric model that is formulated from the perspective of what the Tibetan traditions call highest yoga tantra (Tib., bla na med pa’i rnal ’byor gyi rgyud). For this account, the main purpose of tantric practice is one that we have discussed before: the complete eradication of the fundamental ignorance that, by virtue of distorting our awareness of reality, causes suffering and prevents us from achieving the full awakening (Skt., samyaksaṃbodhi) of a buddha. Recall also that removing that fundamental cognitive distortion involves cultivating the wisdom that uproots ignorance precisely because it directly cognizes the nature of reality without any such distortion. While the various Tibetan traditions differ somewhat on the details, the Vajrayāna tantric insight is that our gross level of experience contains so many distortions that systematically undoing them can take an extraordinarily long time, on the order of “three incalculable eons,” according to a traditional estimate. Yet if we can somehow experience wisdom at a subtler level of experience that acts as a foundation for the gross level of experience, that subtle level of wisdom can uproot all the gross confusions subserved by that level of consciousness. According to Vajrayāna theory, that kind of experience, which requires diving down to the subtlest levels of consciousness, enables us to achieve full awakening in “a single body, a single lifetime” (Tib., lus gcig tshe gcig).

That subtlest level of consciousness occurs reliably at the moment of death, so tantric technology involves reproducing the experience of death, without actually dying. From the Vajrayāna perspective, the various winds in the body must be manipulated to achieve this feat, but to achieve that level of control, practitioners must first move beyond their “ordinary perceptions and conceptions” (Tib., tha mal kyi snang zhen). This is necessary because the processes of perceiving and thinking are constituted by the fluctuations of these winds in various channels, and those fluctuations follow the deeply habituated patterns that manifest as our ordinary identities. Hence, before attempting to manipulate the winds, practitioners must first disrupt those deeply ingrained patterns, and to do so, they engage in the generation stage (Skt., utpattikrama), the first phase of practice in the Vajrayāna style discussed by our authors. By transforming their sense of identity through elaborate visualizations, recitations, and rituals, tantric practitioners transform their identities in ways that make the energy winds available for manipulation. When they reach that point, practitioners are ready for the next phase of practice, the completion stage (sampannakrama).

When tantric practitioners engage in the completion stage, they employ techniques to actually manipulate the winds, with the eventual goal of inducing a “dissolution” sequence said to closely resemble the process of dying. In actual death, the physical processes associated with the gross elements “dissolve” or cease to operate, and although the physical body is still present, its coarse functions such as digestion have ceased. As this process continues, only the energy winds remain functional, and as these also dissipate, conceptual and affective processes also shut down. The final stages of death involve just three progressively subtler forms of wind that are inseparable from three progressively subtler levels of consciousness. If awareness can be sustained through this process, various phenomenological appearances are said to occur, and in the final step, all that remains is an extremely subtle form of wind-mind called the clear light (Tib., ’od gsal, Skt., prabhāsvara).

In actual death, it is said that all of the winds dissipate, and the clear-light wind-mind that marks the end of this process must also decay; by that point, the process is long-since irreversible, and death is inevitable. In Vajrayāna practice, practitioners use techniques that induce a simulation of this process, without actually allowing it to end in death. In so doing, these practitioners learn to access what is said to be the subtlest level of conscious awareness. Ordinary persons, if they somehow could sustain awareness into the clear light, would still experience that state with the distortions that come from ignorance, but tantric practitioners are said to have the training to see that clear-light wind-mind in its true nature, thus counteracting ignorance at the very subtlest level of consciousness. In a sense, the clear-light wind-mind is the foundation for all other levels of consciousness, so counteracting ignorance at that level has a tremendous impact, potentially leading directly to buddhahood itself.

The clear-light state induced through tantric practice is said to be both extremely subtle and also extremely intense or even “blissful,” and these account for its tremendous potential for transformation. Nevertheless, the practice-induced clear-light state is said to be “metaphorical” (Tib., dpe’i ’od gsal) in relation to the actual clear-light wind-mind that occurs in true death. For Vajrayāna practitioners, harnessing the extreme subtlety and power of the metaphorical clear-light mind to the task of uprooting ignorance is certainly part of the goal while they are alive, but inducing that state has another purpose: it prepares practitioners for death and the opportunity to bring their contemplative practice into the actual clear-light mind itself.

John Dunne

"In a sense, the clear-light wind-mind is the foundation for all other levels of consciousness."

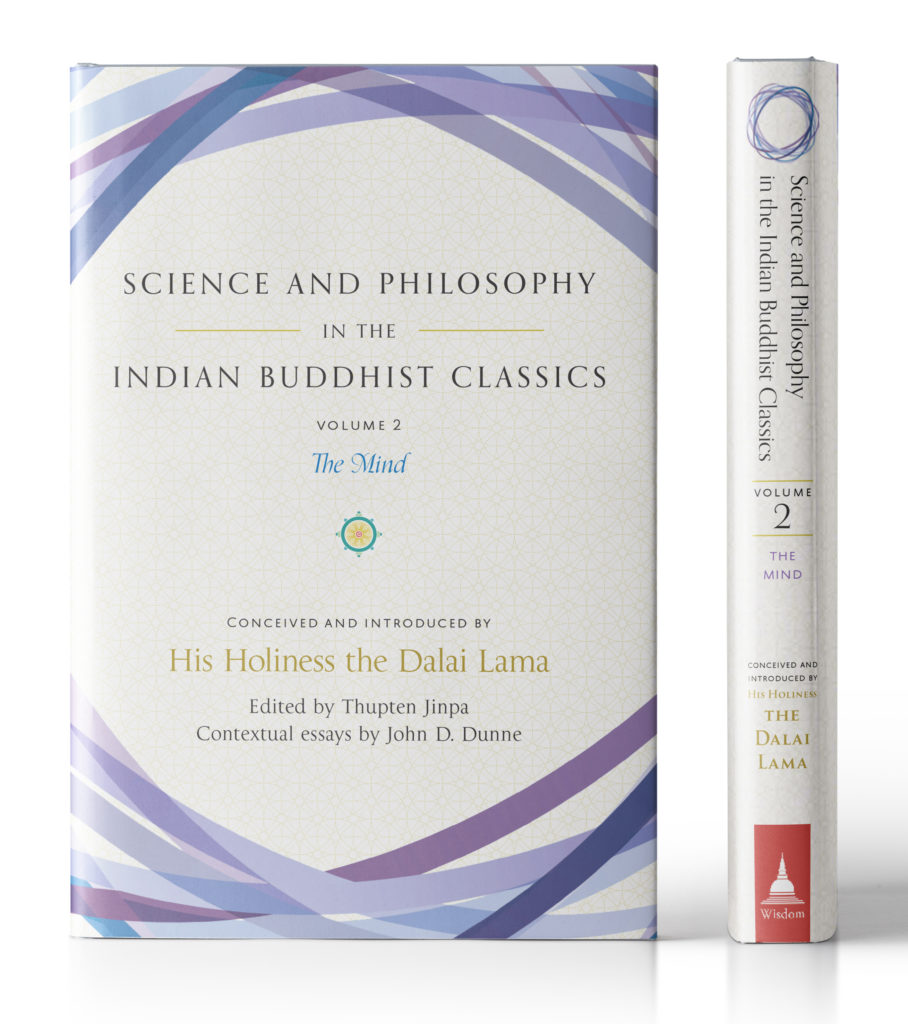

This, the second volume in the Science and Philosophy in the Indian Buddhist Classics series, focuses on the science of mind. Readers are first introduced to Buddhist conceptions of mind and consciousness and then led through traditional presentations of mental phenomena to reveal a Buddhist vision of the inner world with fascinating implications for the contemporary disciplines of cognitive science, psychology, emotion research, and philosophy of mind. Major topics include:

This, the second volume in the Science and Philosophy in the Indian Buddhist Classics series, focuses on the science of mind. Readers are first introduced to Buddhist conceptions of mind and consciousness and then led through traditional presentations of mental phenomena to reveal a Buddhist vision of the inner world with fascinating implications for the contemporary disciplines of cognitive science, psychology, emotion research, and philosophy of mind. Major topics include:

– The distinction between sensory and conceptual processes and the pan-Indian notion of mental consciousness

– Mental factors—specific mental states such as attention, mindfulness, and compassion—and how they relate to one another

– The unique tantric theory of subtle levels of consciousness, their connection to the subtle energies, or “winds,” that flow through channels in the human body, and what happens to each when the body and mind dissolve at the time of death

– The seven types of mental states and how they impact the process of perception

– Styles of reasoning, which Buddhists understand as a valid avenue for acquiring sound knowledge

In the final section, the volume offers what might be called Buddhist contemplative science, a presentation of the classical Buddhist understanding of the psychology behind meditation and other forms of mental training.

To present these specific ideas and their rationale, the volume weaves together passages from the works of great Buddhist thinkers like Asaṅga, Vasubandhu, Nāgārjuna, Dignāga, and Dharmakīrti. His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s introduction outlines scientific and philosophical thinking in the history of the Buddhist tradition. To provide additional context for Western readers, each of the six major topics is introduced with an essay by John D. Dunne, distinguished professor of Buddhist philosophy and contemplative practice at the University of Wisconsin. These essays connect the traditional material to contemporary debates and Western parallels, and provide helpful suggestions for further reading.

| There are no products in your cart. |