The following is a transcript from lesson 8 of the Wisdom Academy online course The Foundations of Mindfulness, taught by Bhikkhu Anālayo. In this part of the lesson, Ven. Anālayo engages Jon Kabat-Zinn, founder of MBSR (mindfulness-based stress reduction), in a conversation about mindfulness and health. This interview was filmed at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. Minor edits have been made to improve readability.

Bhikkhu Anālayo: Our topic today is contemplation of feeling. And in my instruction, based on the canonical instruction of distinguishing the three affective tones of leaving pleasant, unpleasant, neutral, I place particular emphasis on the potential of exploring the conditioner that you’re feeling. With the case of painful feelings, the instruction is to observe in a posture, pains, or an itch, to just watch it before taking action. I’m very glad today to be able to discuss this topic with my dear friend Jon Kabat-Zinn, who has very kindly agreed to dialogue with me on this topic, and I was hoping that you might get us started by telling a little bit about your own experience. Maybe you did have experience with pain, and how this led you to a vision that I think has transformed the world.

Jon Kabat-Zinn: Well, thank you. It’s a pleasure to be here in conversation with you. Yeah, it was on my first extended two-week exposure to the tradition of Ba Khin, that particular lineage. We were on retreat in a freezing cold environment with no heat for two weeks, taking vows not to move for up to two or three hours at a time. [And this was] for people who did not have that much experience in long-term practice.

And so I wound up with a teacher who was very much like a Marine Corps drill instructor. So it was just very hardcore teaching. And I wound up having experiences of discomfort on that retreat which were extraordinary. But I was also at that time young enough to have a very strong, kind of almost militaristic, sense of toughness. You know, we can just tough it out. And so I would try to make room for these sensations that ordinarily I had to at one time get up and shift my posture for, and discover that it was possible to actually put out a welcome mat for these totally unwanted sensations in the body. And although the thought in the mind was that they were intolerable, to actually check in a moment and ask: is this killing me right in this moment? To investigate.

And what I discovered for myself was that no, in this moment it’s not killing me, but what about the next one? . . . this moment, it’s very, very intense. And it was also a way in which I can embrace it, that it’s okay. So that was a very powerful lesson for me, [a] teaching for me, because I realized that I could end the pain experience by simply getting up and saying, I’ve had enough. I’m not gonna do this anymore. But there are people living on this planet who can’t simply get up and have their pain go away. So I thought, wow, this is an incredibly powerful way to learn how to live with the unwanted. With things that ordinarily you would never dream of being able to tolerate, and having no motivation to in fact tolerate. And then, here is a place where not only can it be tolerated on the surface, but it actually turns out that you don’t need to tolerate it. . . . you can actually welcome it and simply let it be as it is, and then not generate a big story of “this is killing me” and so forth. So that was one element that, you know, went into my longer enterprise of meditating on, the potential to bring mindfulness into the mainstream of medicine and healthcare.

That was just one particular retreat, one particular moment. but it showed me something that I’ve never really forgotten, which is that it’s possible to turn towards what you most want to run away from. And then the whole landscape changes when you do that, because there was something in you, in me, that was recognizing that that sensation was not my sensation. And therefore I was already free of it in that moment. It’s not like I had to tolerate it and get good at grinning and bearing it and then it would go away. But no, at its most intense, I can be equanimous about it. And it wasn’t a thought, it was a direct experience.

"If you are willing to turn towards what you most want to run away from, there's a lot to be learned there."

Bhikkhu Anālayo: So that is precisely this uncoupling of the actual sensation of pain from all the emotional repercussions. Taking the ground of anything I’m making, out from emotions.

Jon Kabat-Zinn: Beautifully said. And I love that word uncoupling much better than decoupling, although I guess they mean the same thing. But what we’re really talking about is pain. In a scientific pain framework, there are different elements to what makes up an experience of pain in a particular moment.

So there’s the sensory dimension, what they call the nociceptive dimension. Then there’s the cognitive dimension, that is, your stories about your experience. And then there’s the emotional element that gets into it. And what I saw happening in front of my eyes and in my body was that there was an uncoupling, a natural uncoupling of the sensory dimension from all of the education going on in the cognitions and the emotion. . . . they uncoupled, and all of a sudden there’s no problem. Yeah, you still got the intense sensations. It’s not like they go away, but your relationship to it is completely transformed.

And part of that is attitudinal. No one can force you to do that. But if you are willing to turn towards what you most want to run away from, there’s a lot to be learned there. And to me, that’s kind of the interface where the meditation practice comes to life . . . once you come to that kind of condition, freezing cold, meditating for hours at a time, then the liberated moment would be realizing that you asked for this too.

You can always fight it if you want to, but why not treat it as a laboratory and dive right in and see what the hidden dimensions of this experience are, instead of just reacting and not liking what’s happening, and taking it very personally.

Bhikkhu Anālayo: I think that’s the point about taking it not intensely personal. That’s the key.

Jon Kabat-Zinn: Yes. It’s not my knee anymore, or my back, or my back pain, or my story of how much I loved this retreat until this moment. Those narratives are really incomplete and very small compared to the larger narrative of Who was it that signed up for this retreat in the first place? And why have you stayed up till this moment? There is some kind of deep longing, yearning for liberation, freedom, that often gets us to the retreat, but then we forget about it . . . [that longing] needs to be instantiated virtually in-breath by in-breath, and out-breath by out-breath.

Bhikkhu Anālayo: But if the key is that insight into emptiness, how do you communicate this to people who have no background in Buddhism at all?

"Don't take personally things that are not really personal."

Jon Kabat-Zinn: That’s a good question . . . one thing I’ll say a lot is, don’t take personally things that are not really personal, and that becomes a koan. Because, well, what’s not really personal? And as soon as you start thinking about it, nothing is really personal, then you have that direct insight into emptiness, at least on the cognitive level.

As I understand it, in the teachings of the vedanas, the whole point is to apply mindfulness at the point of contact so that it doesn’t go from the feeling to the craving. How do you actually liberate that process, so that it comes to a stop and you don’t get into, “I want more of this” if it’s pleasant, and “get me out of here” if it’s unpleasant? And if it’s neutral, then you don’t even notice it.

There’s a fairy tale that actually talks about this: once upon a time, there was a princess who lived in a wonderful palace with her father, the king—and nothing much is said about the queen, so we already know that something is going on there. And one day the princess, when she was maybe 10 or 11, was playing with a group of her friends, and they were on their way to a swimming hole. And on the way there, she stubbed her toe on a rock, and she was, as the fairytale says, “sorely vexed.”

And being the princess, she knew that she could ask her father for anything, and she decided that it would be a good idea to pave the entire kingdom with leather so that nobody would ever have to suffer the indignity and pain of a stubbed toe ever again.

So she goes to the king to ask that. But luckily the minister was there, who kind of saw what was brewing, and when the princess asked the king to pave the entire kingdom over with leather, the prime minister interjected, “Your Highness, that is a very powerful idea. Of course nobody should suffer the indignity of a stubbed toe, but perhaps there would be unforeseen consequences if we covered the entire kingdom with leather, to say nothing of the fact of how are we going to eat? But perhaps it would serve the function just as well if we took leather and cut it out in the form of the princess’ foot, and took other leather strands and wove them together so that the piece of leather stayed on the sole of her foot. And then she could go around all over the place and not stub her toe.” And so that’s said to be how the shoe was invented. But the point is, it’s applying mindfulness at the point of contact and that itself liberates the problem.

Bhikkhu Anālayo: It does. It does. I would like to take up, also in relation to pain, what I myself find such a powerful insight: that the body is actually a constant source of pain. And that so much of what we do is just to alleviate that pain. And the other side of that coin: whenever I get sick, then this is something that is almost unfair. I shouldn’t get sick. I’m always puzzled, when I teach this extremely important point, that it doesn’t seem to find much resonance. What you have found?

"The whole point is to apply mindfulness at the point of contact so that it doesn't go from the feeling to the craving."

Jon Kabat-Zinn: I think it’s a fairly modern perspective, because medicine has been so successful. There’s a sense that health should be your normal default mode. And in an ideal world it would be. But given that genetics and happenstance play a very big role in life, there’s really no rational expectation that one will live one’s entire life in the state of perfect health of body, mind, and heart. And so there is this sort of sense of self that arises, that’s like, “I deserve to be healthy” or whatever it is, or “I am healthy,” and you start to claim responsibility for something that’s really just a gift, if not an accident.

And people who come down with horrible diseases—it’s bad luck. Or sometimes it’s just being in the wrong place at the wrong time, having an accident of one kind or another, and then suffering. So in some sense, I think the Buddha’s certainly got it right that dukkha—suffering, and all the other meanings of dukkha—really is the underlying fabric of a lived experience in this world. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s bad. It means we now have to find effective ways to be in wise relationship to it. And so one would be befriending it.

I know you teach that, for instance, our impulse to feed the body—where does that come from? Most of us eat long before we’re driven to it by hunger. But the ultimate cause of eating is hunger, and hunger is a source of pain. It’s a form of pain. First, it needs to be satisfied. Of course we satisfy it a thousand times more than the actual biological need, but still. And then there’s the eliminator functions in the body. If we don’t eliminate, then we have pain at that end. So whether it’s coming in or whether it’s going out, from one particular perspective, you could see this as just a giant bundle of potential problems. And of course that’s what it means to be alive.

But the problem is, if we take it too seriously and then build up a narrative about how this is not supposed to happen to me, then that’s a direct invitation for suffering. If you don’t take it personally, then you learn to make space for what you most don’t want to experience, because it’s already here in a sense. So whether you want to experience it or not—it’s not really germane or relevant. And that is actually a source of reclaiming life, because then there’s no problem with eating. There’s no problem with going to the bathroom. The problem is not wanting things to be as they are. And then at a certain point, of course, the body dissolves and dies, and we think, “Why does this happen to me? Just because it’s happening to everybody else? Why? No! It wasn’t supposed to happen now, it’s supposed to happen 20 years from now, in my fairy-tale with myself.” So any way you look at it, the more you can be in touch with the feeling tone of pleasant, and what happens to you when pleasant arises—you have been trained into more of that. Unpleasant arises, and aversion comes up, and then you hold the space of just being, pure awareness.

"Suffering is the underlying fabric of a lived experience in this world. That doesn't mean it's bad."

Then they don’t have any grip over you anymore. And even the subtlety of the middle. Oh, and you make that beautiful point that they are actually a continuum. It’s not just pleasant and unpleasant—that’s a dualism. There’s a continuity, right through from one to the other. In the middle is the neither pleasant nor unpleasant. And for most of us, we tune that out immediately, because it’s so boring. Or we think it’s boring, because there’s no seduction. There’s no like “More for me” or “That’s horrible, I’m going to have to fight with that.” So we sleepwalk through a lot of life, because it’s not satisfying our desires.

So as soon as you see that, then you have one more degree of freedom in handling life experience, which is: “I can sort of buy into just being bored, or having to fill my life with more and more interesting seductive events, and trying to run away as much as possible from bad luck, including dying and aging and everything else—or I can put out the welcome mat for the entirety of it, and live in this moment with things exactly as they are, and see what happens in the next moment.

Now, ironically, biologically, just that has huge consequences in the body and in the mind, and probably for health. So the non-doing, in the apparent non-doing of meditative practice, actually every atom and molecule and neuron in your body is listening in to this, and your genes. And there’s evidence that our biology is actually changing in relationship to how we hold the present moment.

But does that in some sense becomes what the neuroscientists would call the default mode of living? What is our least common denominator? One of wakefulness? Or is it one of being lost in thought? Awareness, or thinking, thinking, thinking?

Obviously awareness is bigger than thinking because it can hold any and all thought.

To me, that feels like a key affirmation for regular people. Where the rubber meets the road is when something arises that we actually take note of—whether it is pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral—and then be aware of the seduction, aversion, imprisonment—and then choose not to walk in.

And we’ll get a million chances a day to do that. It becomes a kind of its own form of adventuring in the field of what it really means to be human. And to have a body, and to inevitably have to face moments that are just full of uh, of pain and, and to differentiate in a deep way, not really a cognitive way, pain from suffering. Does this make any sense to you?

"What is our least common denominator? One of wakefulness? Or is it one of being lost in thought?"

Bhikkhu Anālayo: It fits totally with my own experience. I have a chronic pain condition, and this has been one of my greatest teachers, in the sense that actually realizing that it is a baseline condition of the body to give rise to pain has completely transformed my relationship to it. And this is why I can live as a monastic, and why I really try to bring [mindfulness practice] down to what’s really involved, like eating. It’s really about nourishing the body and not about entertaining the taste buds. And that’s why I think this working with pain is so powerful, because it really clarifies priorities and shows what type of attitude to bring to pain. And from that it moves over to the other feelings. And for me, the pain one is really the one where we can get things really clarified. What is the nature of the body, what is the nature of pain? When I am teaching and I say the body is a source of pain, [the students] go: “Ugh.” And then I say there’s another feeling, that’s a pleasant one, and they go: “What is it!?” . . . [we’re] not chucking the body out and saying, you’re the bad guy, we don’t want you—rather, an embodied presence of mindfulness [can be] a source for the mental feeling of pleasure of being in the present moment.

Jon Kabat-Zinn: So let me ask you: in your body, with your chronic pain condition, what is your experience of that from inside the body, bringing that attitude towards it? Is it one of friendliness? Is it one of befriending? Being friendly to the sort of physicality of the body that causes pain?

Bhikkhu Anālayo: Well it is no longer pain, it is just a sensation. It is a condition where I can’t sleep at night and I wake up because of the pain and I can’t sleep anymore. And I simply make space around it.

Jon Kabat-Zinn: So even not being able to get to sleep is not a cause for frustration and contraction?

Bhikkhu Anālayo: No, because I’m not taking it in as I am in pain, I cannot sleep. It’s just that’s what’s there, thank you for reminding me.

Jon Kabat-Zinn: And then you’ll sleep when you can.

Bhikkhu Anālayo: That’s right. But even if I cannot sleep for several hours, I’m so relaxed that it doesn’t make much of a difference.

Jon Kabat-Zinn: Well there’s an interesting thing there, because there’s sleep, which is supposed to be restorative and restful, and then there’s resting in wakefulness. Then you get the benefit in a certain way if you’re not attached to “I have to sleep now because I got a big thing to do in the morning,” but almost all of us are very attached to getting enough sleep.

Bhikkhu Anālayo: Oh, I am also attached to that. It’s just that I found that was the most meaningful way for me to turn this part of my life experience into something that’s productive of insight, and at the same time, use it in such a way that it works best. Because: “Oh my God, tomorrow I have to teach the class and I have to sit down, I’m already tired, and the back is so bad, and why is it like that and why do—”

Jon Kabat-Zinn: How do you know all those stories?

[Laughter.]

Jon Kabat-Zinn: Well, part of being human is that people project onto anybody who’s a meditation teacher that they’ve transcended all of that stuff. But it’s a big romance because in some sense that too is another narrative. And it’s really very important that people know that what you’re describing is a very human way to be in relationship with something you didn’t ask for, and certainly [you] would be happy to have disappear. But most of us, we need sleep, and we’ll make major stories around not getting enough sleep and then not being able to function the next day. But that’s a choice. And it really has to do with not a philosophy of life, but right in that moment being willing to find a new way to be in relationship to something that ordinarily you wouldn’t want to have present. But it is present.

© 2020 Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. Click here to learn more about the Foundations of Mindfulness online course.

| × |

|

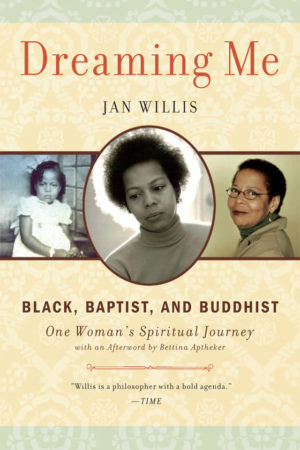

Dreaming Me - eBook

1

x $19.99 |